Martian moon Phobos is not long for this Universe.

According to astronomers' calculations, the potato-shaped satellite is drawing slowly, but inexorably, closer to its host planet. Eventually, within about 100 million years, the gravitational interaction between the two bodies will tear Phobos apart, giving the red planet a temporary dusty ring.

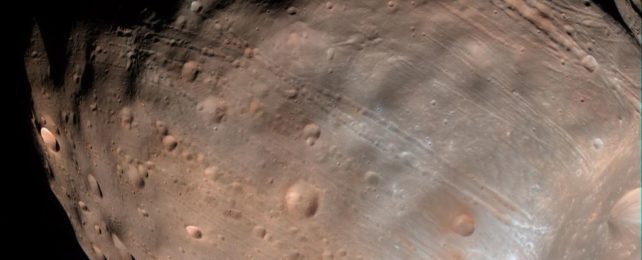

According to a new study, those gravitational interactions may already be having an observable effect. At least some of the mysterious, parallel shallow grooves that cover the moon's entire surface could be the result of fracturing as its orbit slowly decays and tidal forces tug ever harder at its bones.

"Our analysis supports a layered heterogeneous structure for Phobos with possible underlying failure-induced fractures, as the precursor of the eventual demise of the de-orbiting satellite," write a team of astronomers led by Bin Cheng of Tsinghua University in China and the University of Arizona.

Tidal forces that pull on bodies in a system are the result of their gravitational interaction, stretching their structures along an axis that runs between them.

Usually, any significant effect this distortion might have on a solid surface is pretty small. Where tidal forces can be easily observed in the movements of our planet's liquid oceans, visible effects on masses of land are less obvious.

That doesn't mean tidal forces between other solid bodies can't have more obvious consequences. Stretching caused by tidal forces can in some cases cause stress fracturing. We've seen this in Saturn's moon Enceladus, whose icy shell has deep, parallel fractures at its south pole caused by tidal stress.

With an orbit of just 7 hours and 39 minutes, Phobos is pretty close to Mars, drawing closer at a rate of around 1.8 centimeters per year. At that proximity, it's absolutely possible that tidal forces could induce surface fracturing on its 27 kilometer- (16.8 mile-) wide body. The idea that Phobos' stripes are the result of such an interaction has also been previously considered and found plausible.

However, it's unclear whether the current configuration and interaction of Phobos and Mars could produce the observed striping, and other explanations are also in the running. For instance, a 2018 study found that the stripes could be the result of rolling boulders.

So Cheng and his colleagues conducted 3D mathematical modeling explicitly examining the tidal stretching and squeezing of a layered Phobos-like body, with a loose rubbly exterior sitting over a cohesive layer below.

The researchers performed hundreds of simulations using their model. In a significant number of these simulations, tidal forces caused the cohesive layer to split and fracture in parallel grooves, causing the upper loose regolith to drain into the fractures below. The result is a stripey, striated surface very similar to regions observed on Phobos.

Not all areas of Phobos were consistent with the model, the team found. In particular, grooves around the moon's equator didn't match predictions. But the results do show that at least some of the stripes could be caused by fracturing as the moon spirals towards death by tidal disembowelment. This would mean that we are seeing the beginning of the end for Phobos.

These results, therefore, could have implications for studying other moons that are experiencing significant orbital decay, such as Neptune's moon Triton. The draining rubble could also expose pristine material on Phobos, could make the grooves a very interesting region of study for the upcoming Mars moon mission by the Japanese Space Agency.

This mission is expected to deliver conclusive evidence of the origin of these mysterious stripes – but tidal disruption is certainly appearing to be an intriguing possibility.

"Modeling Phobos as a rubble-pile interior overlaid by a cohesive layer, we find that the tidal strain could create parallel fissures with regular spacing," the researchers write in their paper.

"Our analysis suggests that some of the grooves lining the surface of Phobos are likely early signs of the eventual demise of the de-orbiting satellite."

Mashed potato, anyone?

The research has been published in The Planetary Science Journal.