Scientists may have just found a major new clue that could help solve the frustrating and ongoing mystery of the migraine.

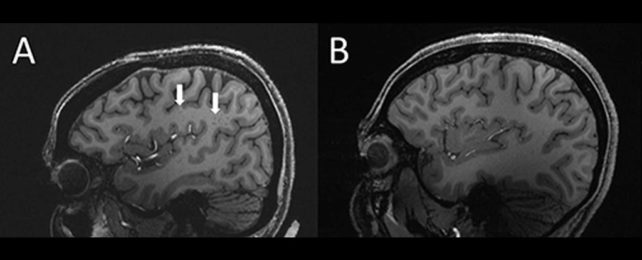

Using ultra-high-resolution MRI, researchers found that perivascular spaces – fluid-filled spaces around the brain's blood vessels – are unusually enlarged in patients who experience both chronic and episodic migraine.

Although the link to or role in migraine is yet to be established, the finding could represent an as-yet unexplored avenue for future research.

The discovery was presented at the 108th Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

"In people with chronic migraine and episodic migraine without aura, there are significant changes in the perivascular spaces of a brain region called the centrum semiovale," says medical scientist Wilson Xu of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

"These changes have never been reported before."

Migraine, let's not mince words, is hell to live with. Although the excruciating headache aspect of it is well known, migraine can also cause vertigo, visual impairment (known as aura), photosensitivity, and nausea to the point of vomiting. It's unknown what causes migraine, there's no cure, and in many cases, the condition is unresponsive to treatment.

The condition affects an estimated 10 percent of the global population. So finding a cause and more effective management strategies would improve the lives of millions.

Xu and his colleagues were curious about the perivascular spaces in the centrum semiovale, the central region of brain white matter directly below the cerebral cortex. The function of these spaces is not completely understood; they do play a role in fluid movement drainage, and their enlargement can be a symptom of a larger problem.

"Perivascular spaces are part of a fluid clearance system in the brain," Xu says. "Studying how they contribute to migraine could help us better understand the complexities of how migraines occur."

He and his colleagues recruited 20 patients between the ages of 25 and 60 with migraine: 10 who experience chronic migraine without aura, and 10 who experience episodic migraine. In addition, 5 healthy patients who don't experience migraines were included as a control group.

The team ruled out patients with cognitive impairment, claustrophobia, brain tumor, or who had previously had brain surgery. Then, they conducted MRI scans using an ultra-high-field MRI with a 7-tesla magnet. Most hospital scanners only have magnets up to 3 tesla.

"To our knowledge, this is [the] first study using ultra-high-resolution MRI to study microvascular changes in the brain due to migraine, particularly in perivascular spaces," Xu explains.

"Because 7T MRI is able to create images of the brain with much higher resolution and better quality than other MRI types, it can be used to demonstrate much smaller changes that happen in brain tissue after a migraine."

The scans revealed that the perivascular spaces in the centrum semiovale of patients with migraine were significantly enlarged compared to the control group.

Researchers also found a difference in the distribution of a type of lesion known as white matter hyperintensities in migraine patients. These are caused by tiny patches of dead or partially dead tissue starved by a curtailed blood flow, and they're pretty normal.

There was no difference in the frequency of these lesions between the migraine patients and the control patients, but the severity of deep lesions in migraine sufferers was higher.

This suggests, the researchers believe, that the enlargement of perivascular spaces could lead to future development of more white matter lesions.

Although the nature of the link between enlarged perivascular spaces and migraine is unclear, the results suggest that migraine comes with a problem with the brain's plumbing – the glymphatic system responsible for waste clearance in the brain and nervous system. It utilizes perivascular channels for transport.

More work is needed to explore this correlation, but even identifying it is promising.

"The results of our study could help inspire future, larger-scale studies to continue investigating how changes in the brain's microscopic vessels and blood supply contribute to different migraine types," Xu says.

"Eventually, this could help us develop new, personalized ways to diagnose and treat migraine."

The research has been presented at the 108th Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.