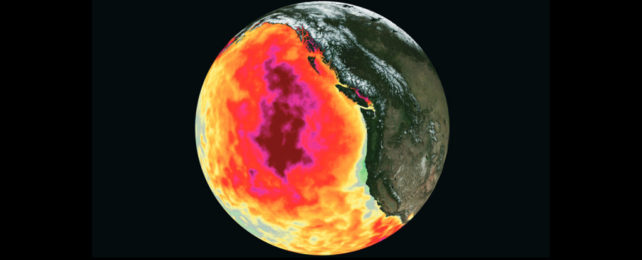

Nicknamed 'the Blob', a large patch of abnormally warm water covering a section of the Pacific Ocean from 2014 to 2016 behaved just like a B-grade horror movie, having a devastating impact on a wide variety of species.

A new study on the Santa Barbara Channel off the Californian coast highlights how this environmental horror show continues to affect marine ecosystems.

The Blob caused significant shifts in aquatic ecosystems at the time, particularly impacting sessile animals, those stuck in place like anemones. This latest research shows that six years later, underwater populations inhabiting the kelp forest ecosystem still aren't back to where they were.

While the levels of sessile invertebrates – filter feeders attached to reefs – have bounced back overall, the numbers belonging to the invasive species Watersipora subatra (a recent arrival) and Bugula neritina (a long-term resident) have boomed. These are types of bryozoans; tiny, colonial, tentacled animals that essentially act together in groups as a single organism.

"The groups of animals that seemed to be the winners, at least during the warm period, were longer-lived species, like clams and sea anemones," says ecologist Kristen Michaud, from the University of California, Santa Barbara.

"But after the Blob, the story is a little different. Bryozoan cover increased quite rapidly, and there are two species of invasive bryozoans that are now much more abundant."

The numbers of sessile invertebrates saw an initial drop of 71 percent across 2015 when the Blob took hold, as the warmer water meant creatures like anemones, tubeworms, and clams run out of phytoplankton to feed on.

Plankton relies on nutrients brought up by colder water, which was limited thanks to the warm water's presence. The metabolisms of these sessile invertebrates was increased by the heat too, meaning they needed even more of the food they weren't getting.

Several causes could be responsible for the dominance of W. subatra and B. neritina, the researchers say: they include the ability to survive at higher temperatures, and to compete more aggressively for space on reefs. In addition, the ongoing resilience of kelp forests in the region possibly helped to clear space for these bryozoans.

Another native sessile gastropod known as the scaled worm snail (Thylacodes squamigerous) has also been doing well, most likely because it's better able to tolerate warmer waters, and because its food source options go beyond plankton.

The problem with these changes is that the newcomers do not play the same role in the ecosystem as the species they've replaced. For example, the bryozoans are shorter-lived and experience rapid growth, and aren't as adept at surviving the less intense but more prolonged periods of warming as those animals they've replaced.

"This pattern in the community structure has persisted for the entire post-Blob period, suggesting that this might be more of a long-term shift in the assemblage of benthic animals," says Michaud. "These communities may continue to change as we experience more marine heat waves and continued warming."

The water in the Santa Barbara Channel often undergoes temperature fluctuations, such as those caused by El Niño events. However, unlike the Blob, these events are also accompanied by significant wave and storm action – which, for example, rip out kelp forest coverings.

While the reefs have shown they're capable of bouncing back from these warmer periods, the Blob increased temperatures without whipping the seas into a frenzy. That makes it a very interesting period for researchers to study, not least because ocean temperatures continue to rise due to global warming.

The region has been carefully monitored for decades, and that monitoring will continue. The researchers expect the ongoing effects of the Blob to continue, including the ways in which it has an impact on marine species higher up the food chain.

"The Blob is exactly the kind of event that shows why long-term research is so valuable," says marine ecologist Bob Miller, from the University of California, Santa Barbara. "If we had to react to such an event with new research, we would never know what the true effect was."

The research has been published in Communications Biology.