The deserts of Saudi Arabia were once the lush and fertile homes of ancient people more than 8,000 years ago.

Today, the remnants of these long-gone communities still stand – frozen, or rather, desiccated in time.

Right across the Arabian peninsula, from Jordan to Saudi Arabia to Syria, Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Iraq, researchers have identified thousands of huge stone structures from the sky.

The V-shaped arrangements were first noticed by British air force pilots in the 1920s, and for more than a century, experts have debated why they were built.

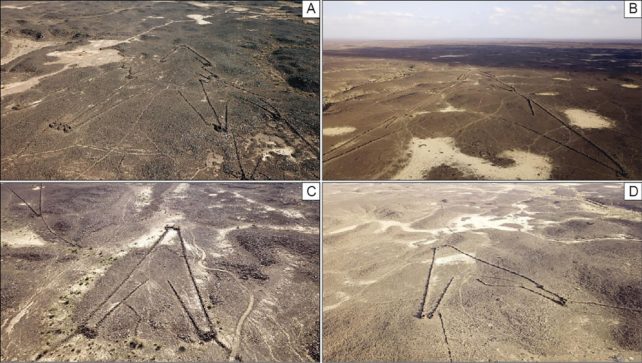

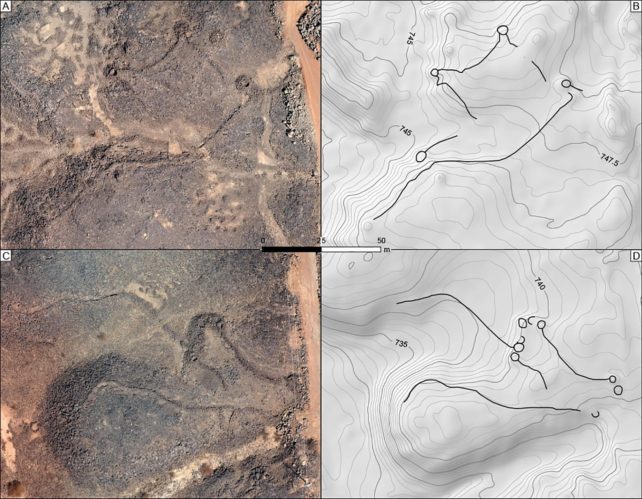

Recent satellite images and drone surveys in the ʿUwayriḍ desert of Saudi Arabia now support a commonly held suspicion.

Today, archaeologists working on these ancient stone patterns, sometimes known as 'desert kites', think they were most likely used as mass hunting traps.

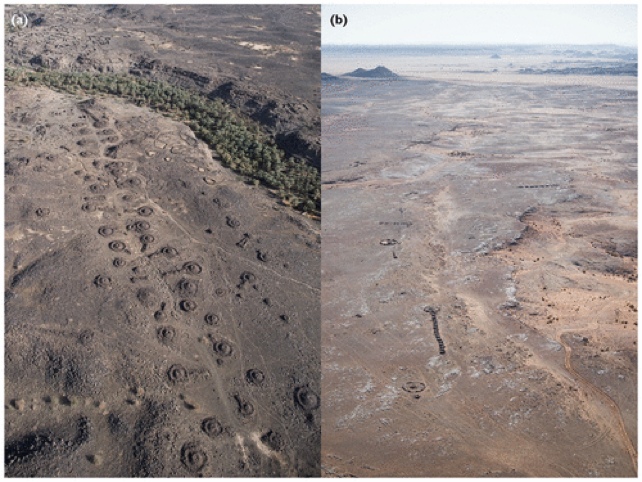

Dozens of previously unknown desert kites found recently in ʿUwayriḍ all seem to be built with the same sort of function in mind.

Some of the V-shapes point to a pit, others to a sudden cliff, and still others to an enclosure.

All three designs suggest desert kites were once used to funnel herds of wild animals to death or captivity.

"The purpose of the form of a kite is generally agreed: animals were driven (an 'active' kite system) or guided (a 'passive' kite system) into a restricted area by the structure's walls," the authors of a new study write.

"Hunting of animals, most commonly gazelle and other herbivorous ungulates, possibly ibex, wild equids, and ostriches, is now accepted as the most common use of these structures."

More excavations are needed to figure out what animals specifically were being herded into the recently discovered traps, but the fact that they show up in other parts of the Arabian peninsula suggests this was a popular and effective strategy for survival.

Further south, for instance, archaeologists have found hundreds of stone kites and thousands of other stone structures dotting the desert.

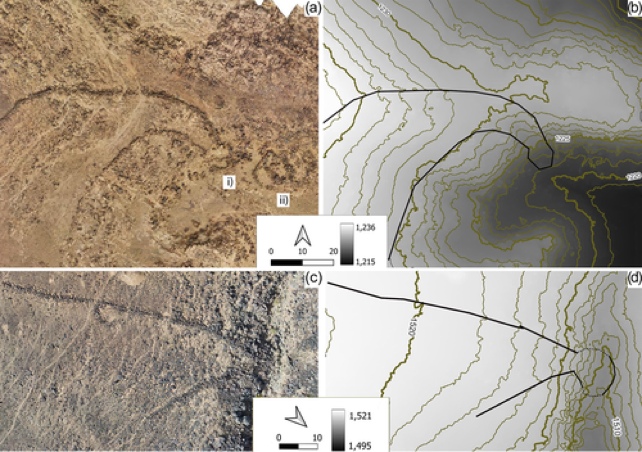

The desert kites further south tend to be more complex and concentrated than those in the ʿUwayriḍ desert. They sometimes combine multiple V-shapes together, as you can see in the image below.

In the past, archaeologists have argued these structures were used as hunting traps because they tend to show up in sandy regions that would have once hosted seasonal grasslands. The greenery would probably have supported migrating gazelle, goats, or other herding animals.

Some ancient rock art images from this time also illustrate kite-like structures being used to funnel animals. The layout of some kites suggest they might have even been used to raise wild animals – one of the first attempts at domestication found anywhere in the world.

Another recent study on desert kites, published in April 2022, points out that a mix of kites in one region is not uncommon. Some of these kites open to pits at the end and others open to enclosures.

"Kites and open kites may have been in operation at the same time, defining related but different hunting techniques," the researchers write.

"They may also have followed each other in time, with one technique leading to the emergence of the other, forms of 'proto-kites' predeveloping the sophisticated and standardized forms of desert kites."

Further research is needed to differentiate between these two possibilities. The snapshot of Neolithic society could ultimately reveal how early humans first began hunting and domesticating animals.

Perhaps getting up close and personal with wild herds is what first allowed our species to breed and raise them as our own.

But not every aspect of these desert kites is necessarily functional.

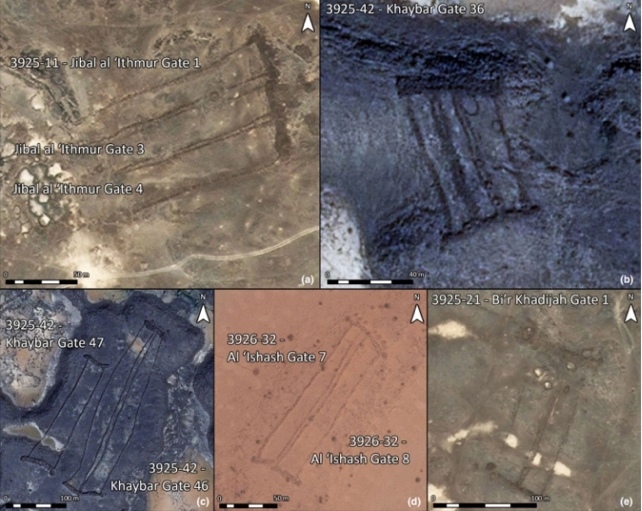

Some kites have been found embedded in even larger stone structures called 'mustatils', which can go for kilometers. Mustatil is the Arabic word for a rectangle, and from above, a block pattern of mustatils looks sort of like a gate.

Despite finding several hundred mustatils in the Arabian desert in recent years, archaeologists don't yet know what they were used for.

They might have been spiritual or cultural monuments for animal sacrifices or feasts, and yet their association with desert kites suggests they could also have been used for corralling animals or storing water.

Whatever they were used for, these stone structures must have been highly effective or cherished. They riddle the region, and initial dating efforts suggest they were in use on the Arabian peninsula for thousands of years.

"Almost nothing is known about mega-traps users in the kite distribution area," write the researchers of the study, published in April.

"More dating is required as well as the excavation of related sites in order to clearly associate them with a cultural facies."

The desert kites of Saudi Arabia have been known about for decades, but they have received surprisingly little attention from the scientific community.

For years now, archaeologists have been calling for more research on the remnants of these ancient communities, and the ball is finally starting to roll.

At the start of 2022, archaeologists working in Saudi Arabia uncovered a 530-kilometer-wide network of lost highways in the nation's northwest.

These ancient roads were lined with thousands of spiraling, stone burial chambers that seemed to lead from one oasis to another.

At many of these oases, desert kites were also found.

The archaeologists who uncovered the highways think they were used by ancient nomadic peoples who were chasing after the best lands and climates.

Thousands of years later, archaeologists are attempting to retrace their steps.

The paper that identified the unknown desert kites was published in Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy.

The review on desert kites was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.