A new analysis of 125,000-year-old bones from around 70 elephants has led to some intriguing new revelations about the Neanderthals of the time: that they could work together to deliberately bring down large prey, and that they gathered in larger groups than previously thought.

The bones belonged to straight-tusked elephants (Palaeoloxodon antiquus), a now extinct species that stood nearly 4 meters (just over 13 feet) tall at the shoulder. That's nearly twice the size of the African elephants that are alive today, and around 4 tons of meat would have been taken from each carcass.

The researchers estimate it would've taken a team of 25 people between 3–5 days to skin and then dry or smoke the elephant meat. It points to either a large group of Neanderthals being nearby, or that they had ways of preserving the colossal volume of meat.

In either case, these early humans start to seem more sophisticated than we'd imagined.

"This is really hard and time-consuming work," Lutz Kindler, an archaeozoologist from the MONREPOS Archaeological Research Center in Germany, told Science.

"Why would you slaughter the whole elephant if you're going to waste half the portions?"

Evidence of charcoal fires around the archaeological site suggest that the meat would have been dried, which is one way of making it last for longer. The haul would have been enough to feed 350 people for a week, or 100 people for a month, according to the researchers – that counters the conventional narrative of Neanderthals living in smaller groups of around 20.

The ages of the animals are telling too. These were almost all adult males – if the hominins were scavenging meat from dead elephants, children and females would be expected. Here, it looks as though they deliberately targeted the larger males for the extra meat, perhaps by driving them into mud or trapping them in pits.

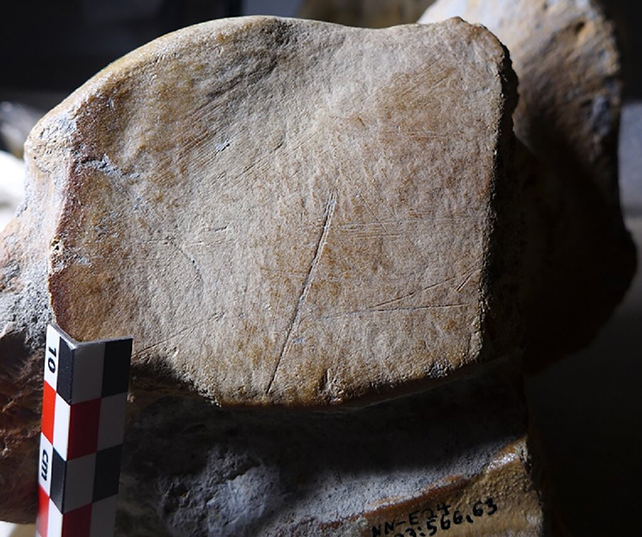

Almost every bone that was examined showed evidence of careful butchery. Marks left by other animals were few and far between, which hints that there wasn't much meat or fat left on these bones by the time the Neanderthals had finished with them.

"It constitutes the earliest unambiguous evidence for the systematic targeting and processing of straight-tusked elephants, the largest Pleistocene terrestrial mammals that ever lived," write the researchers in their published paper.

"This has important implications for our views of Neanderthal local group sizes, mobility, and cooperation."

Around 3,400 elephant bones were studied in total, with researchers finding clear traces of cutting and scraping marks left by flint tools. It's unusual to find direct evidence of cut marks like this, making it an important find.

The site that these bones were taken from sits near the town of Neumark-Nord in Germany, and was discovered by coal miners in the 1980s. It's one of the richest sites we have for studying Neanderthal activities of the Last Interglacial (LIG) period, some 130,000–115,000 years ago.

Our hominin cousins are often portrayed as less intelligent or cultured than the human beings that eventually replaced them, but this study is the latest in a growing pile of evidence that there was more to Neanderthals than we might have thought.

"Neanderthals were not simple slaves of nature, original hippies living off the land," archaeologist Wil Roebroeks, from Leiden University in the Netherlands, told the Associated Press.

"They were actually shaping their environment, by fire… and also by having a big impact on the biggest animals that were around in the world at that time."

The research has been published in Science Advances.