Something strange and rather wonderful happens when two people are working together on the same task, a new study shows: key regions of their brains sync up, suggesting we can match each other's neural activity when we're in groups.

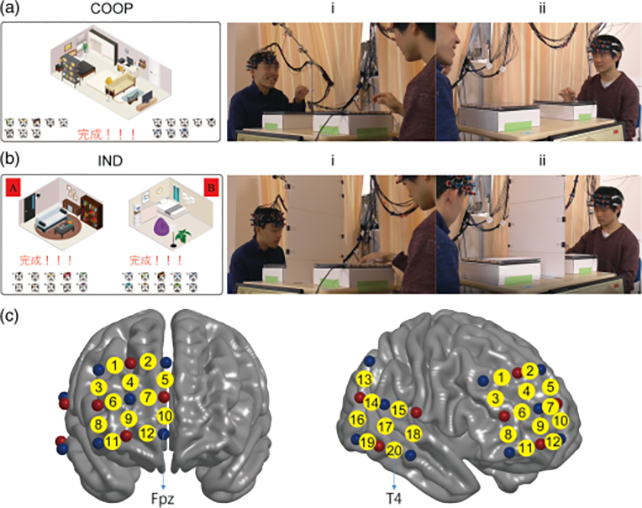

In the study, 39 pairs of volunteers were asked to design the interior of a virtual room together via a touchscreen, until it was satisfactory to both of them. As well as having their brain activity monitored through a functional near-infrared spectroscopy technique, the participants were watched for signs of eye contact.

To study the participants' responses, the researchers developed special processing and modeling techniques capable of recognizing social interactions (the eye contact) and mapping them to particular moments and regions of brain activity.

"Neuron populations within one brain were activated simultaneously with similar neuron populations in the other brain when the participants cooperated to complete the task, as if the two brains functioned together as a single system for creative problem-solving," says psychologist Yasuyo Minagawa, from Keio University in Japan.

The study participants were directed to complete the designated task on their own as well as in pairs, giving the researchers the opportunity to examine both solo brain activity (within-brain synchronizations or WBSs) and group brain activity (between-brain synchronizations or BBSs).

Working together jointly led to "robust" BBS in the superior and middle temporal regions of the brain, as well as specific parts of the prefrontal cortex in the brain's right hemisphere. However, WBS wasn't as strong in the test scenarios.

What's more, the BBSs were shown to be strongest when one of the individuals raised their gaze to look at the other, suggesting an important role here for social interactions. On the other hand, when the volunteers were working on their own, the WBS was much stronger within the same brain regions.

"These phenomena are consistent with the notion of a 'we-mode', in which interacting agents share their minds in a collective fashion and facilitate interaction by accelerating access to the other's cognition," says Minagawa.

The investigation's method is an improvement over previous experiments in 'second-person neuroscience', which simply put two people to work on the same motor task, but scientists will need to find ways of measuring more complex social interactions besides eye contact in the future.

The authors behind this new study think that's possible though – and there is already evidence that some kind of brain synchronization happens when two people are in dialog with each other.

We know that human beings are wired to be social creatures, but there's still a lot we don't understand about how our brains shift when we're in company. As scanning and computing technology improves, we can shed light on those unknowns.

"We could apply our method to more detailed social behaviors in future analyses, such as facial expressions and verbal communication," says Minagawa.

"Our analytical approach can provide insights and avenues for future research in interactive social neuroscience."

The research has been published in Neurophotonics.