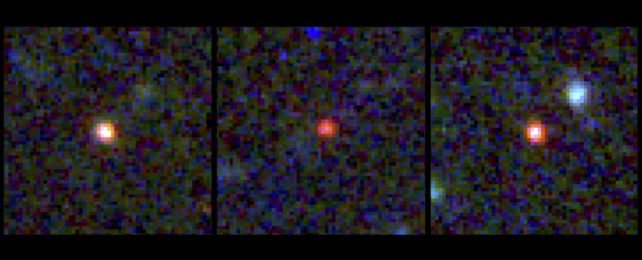

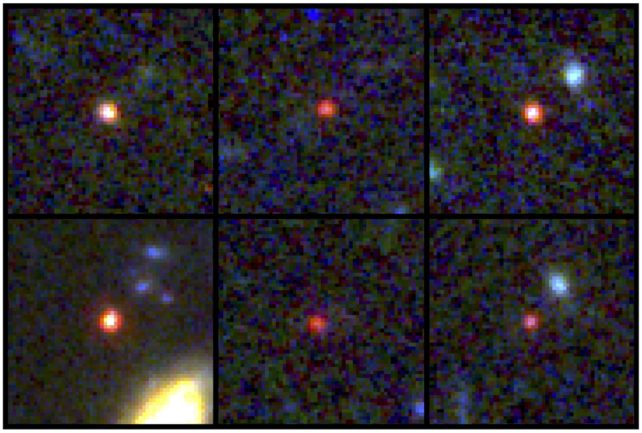

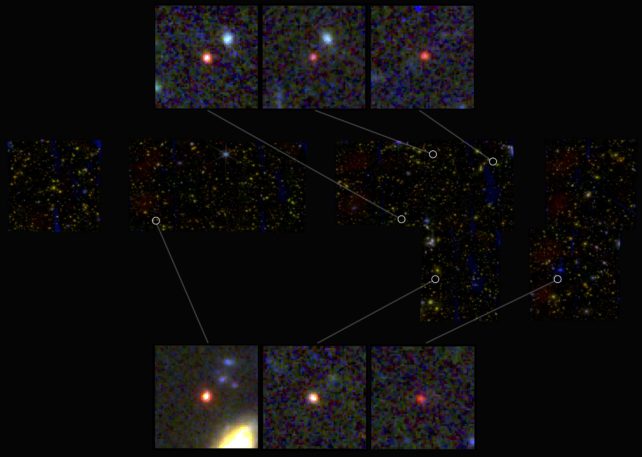

A handful of objects uncovered in JWST data has astronomers stumped.

What's thought to be half a dozen galaxies appear to be massive and well-formed, in spite of appearing as they were just 500 to 700 million years after the Big Bang. Yet according to current cosmological models, there simply wasn't enough time for them to have grown to such a state of relative maturity.

This suggests we're missing a key step or two in our understanding of the evolution of the Universe.

"We've never observed galaxies of this colossal size, this early on after the Big Bang," says astronomer Ivo Labbé of Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, who led the international research effort.

"The six galaxies we found are more than 12 billion years old, only 500 to 700 million years after the Big Bang, reaching sizes up to 100 billion times the mass of our sun. This is too big to even exist within current models. This discovery could transform our understanding of how the earliest galaxies in our Universe formed."

The objects were spotted in observations made by the JWST during its first few months of operation. The powerful space telescope studies the Universe in infrared, which is perfect for spotting the light that has traveled for billions of years to reach us from the early Universe, feeble and stretched out into longer infrared wavelengths by the expansion of space-time.

One of its main objectives is to peer farther into that space-time than any instrument that has come before, and astronomers wasted no time in obtaining the first observations to that end.

"We looked into the very early Universe for the first time and had no idea what we were going to find," says astronomer Joel Leja of Pennsylvania State University. "It turns out we found something so unexpected it actually creates problems for science. It calls the whole picture of early galaxy formation into question."

According to our cosmological models, the very beginning of the Universe was nothing like it is now. First, the hot soup of particles that emerged in the wake of the Big Bang had to cool enough to congeal into atoms, filling the volume of space mostly with hydrogen and helium. It's from this gas that the first stars and galaxies started to form, around 150 million years after the Big Bang.

Observational evidence of this period in our Universe's history has been difficult to obtain, but the timeline is reasonably supported by the evidence we do have. And the timeline suggests that, in the period between around 500 and 700 million years after the Big Bang, galaxies would still have been coming together.

There are a number of reasons why these fully formed galaxies pose a problem. One is that the density of matter within today's largest galaxies vastly exceeds estimates for this time period. Another is that the density of normal matter is coming into tension with the amount of dark matter in the haloes of these galaxies.

The objects are so difficult to explain under current cosmology that the research team has been busy scouring their work for errors. So far, the data and the team's interpretation of it have remained solid, suggesting there is one of two things wrong: our understanding of cosmology, or our understanding of galaxy formation in the early Universe. Either way, the result would mean some significant revision.

"The revelation that massive galaxy formation began extremely early in the history of the Universe upends what many of us had thought was settled science," Leja explains. "We've been informally calling these objects 'Universe breakers' – and they have been living up to their name so far."

It's possible that the objects aren't actually galaxies, but something else. They could, for example, be supermassive black holes of a kind never seen before. Even then, though, the amount of mass concentrated in one place remains difficult to account for so early in the Universe; and that might also mean a revision of our understanding of black holes.

Any one object of this kind would be challenging enough to explain. The discovery of six is setting a chonky cat among the cosmic pigeons. But further investigation is necessary to make sure of what we're looking at.

The next step will be to try to obtain spectra of the candidate galaxies, which will reveal their natures, distances, and sizes in more detail, as well as – hopefully – revealing something of their chemical composition.

"This initial discovery may just be the start of a transformation in how we make sense of the world around us," Labbé says.

The research has been published in Nature.