Earth's atmosphere and oceans are heating up beyond any previous point in human history, triggering a cascade of changes around the planet that our species is racing to manage.

This is due to anthropogenic climate change, of course. Our greenhouse gas emissions are returning to haunt us in various ways, including supercharged hurricanes, heat waves, and other big weather events that affect large numbers of people all at once.

But not all consequences of climate change are so immediately noticeable. According to a new study by an international team of researchers, one lesser-known yet noteworthy effect of warmer seas is the spread of flesh-eating bacteria in coastal waters, where they can dangerously sicken humans even in nice weather.

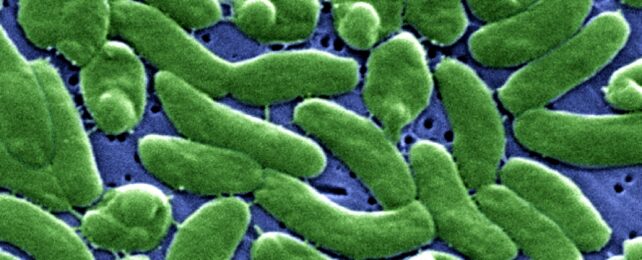

Specifically, the study points to Vibrio vulnificus, a species notorious for infecting humans. It can do so when someone eats raw or undercooked seafood, especially oysters, but it's also capable of life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis when exposed to an open wound.

Long known from coastal waters in the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic coasts of Georgia and Florida, V. vulnificus seems to pose a growing threat in those areas while also colonizing new habitats farther north, the study's authors report.

Over a 30-year span, the number of V. vulnificus infections along the US East Coast rose from 10 to 80 per year, the study found; they may be on track to reach 200 per year by 2100.

Cases also appear farther north every year, the authors add. Once rare north of Georgia on the US Atlantic coast, the bacteria now can be found as far north as Philadelphia.

V. vulnificus infections could begin to plague New York within a few decades, the researchers predict; under medium-to-high scenarios of future emissions and warming, they may occur in every eastern US state by the 2080s.

Their study is the first to map how the sites of V. vulnificus infections along the US coast have changed over time, the researchers say, and the first to examine how climate change might continue to affect its spread in the future.

While the overall number of US infections remains fairly low, the stakes are high: About one in five people with a wound infected by V. vulnificus will die, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), sometimes within a day or two of becoming ill.

Many survivors still require intensive care or limb amputations, the CDC notes.

Led by Elizabeth Archer, a geoscientist at the University of East Anglia in the UK, the study highlights what its authors describe as a growing but underappreciated threat to public health driven by climate change.

"Greenhouse gas emissions from human activity are changing our climate, and the impacts may be especially acute on the world's coastlines, which provide a major boundary between natural ecosystems and human populations and are an important source of human disease," Archer says.

"We show that by the end of the 21st century, V. vulnificus infections will extend further northward, but how far north will depend upon the degree of further warming and therefore on our future greenhouse gas emissions," she adds.

Rising temperatures are already assisting the spread of many pathogenic diseases – including mosquito-borne diseases, for example, and some pathogenic fungi – and that seems to be what's happening with V. vulnificus as coastal waters grow warmer.

Archer and her colleagues used data from the CDC to map out where people caught V. vulnificus infections on the eastern US coastline, allowing them to create a map showing the bacteria's northward spread over the past 30 years.

To map out the future prevalence, researchers used temperature observations and climate models to predict how that spread might continue under various warming scenarios.

"Knowing where cases are likely to occur in the future should help health services plan for the future," says co-author Iain Lake, a professor of environmental science at UEA.

Authorities might develop warning systems that can issue real-time alerts about Vibrio levels, the researchers say, and raise awareness among high-risk groups.

The study was published in Scientific Reports.