Less than one-quarter of Earth's entire ocean floor has been mapped, leaving gaping holes in our understanding of the underwater realm.

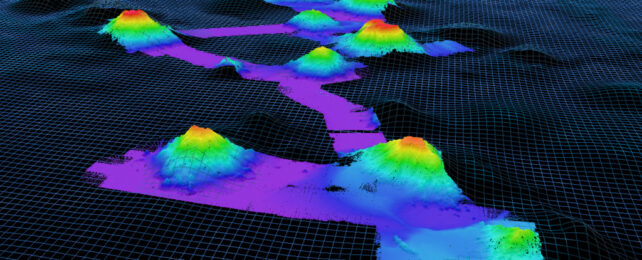

Accidents await in the void: undiscovered seamounts – ancient mountains formed by volcanic activity – can rise thousands of meters in the darkness, putting unsuspecting submarines at risk.

Led by earth scientist Julie Gevorgian of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California, a team of scientists has just discovered more than 19,000 new seamounts using a new batch of satellite data.

That so many underwater peaks have been found brooding beneath the ocean surface is "incredible to think about," Gevorgian told Newsweek.

"Especially when you realize just how big these seamounts are and how they were previously unknown."

Created by volcanic activity deep beneath the ocean's surface, seamounts can rise to around 3 to 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) high. They tend to be easily detectable by sonar, but only if a ship happens to pass over them.

Smaller undersea seamounts less than 2 kilometers tall are even harder to find, though they tend to form near mid-ocean ridges where magma pushes through Earth's thin and fractured crust.

In the past decade or so, scientists have turned to satellite data to detect small bumps in the ocean surface and map where seamounts lie.

Where sonar uses sound waves that ricochet off the seafloor to map its features, satellite altimetry does so indirectly, measuring slight changes in sea surface height that reflect the tug of gravity coming from mounds in Earth's submerged crust. The larger the mound, the more its gravitational pull draws in seawater on top.

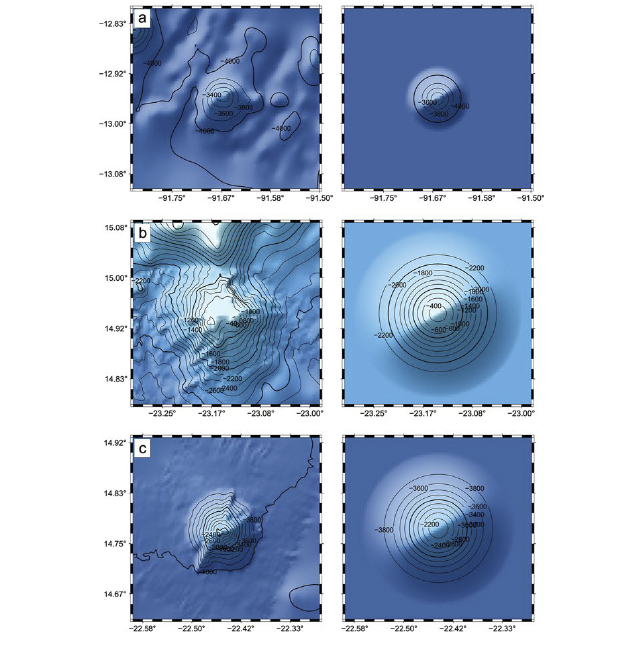

Using this method, Gevorgian and colleagues identified 19,325 new undersea volcanoes, adding to the 24,643 mapped seamounts that two members of the team had previously cataloged back in 2011 and ironing out some mistakes in the process.

That brings the total to 43,454 undersea mountains, almost doubling the number we knew about.

Many of the newly discovered seamounts are on the smaller side, thought to be too small to be detectable in satellite data. However, recent advances to expand coverage and improve the accuracy of satellite data from the European Space Agency's CryoSat-2 satellite and SARAL, the Indian and French space agencies' version, changed the picture.

Of the 700-odd peaks Gevorgian and colleagues discovered in areas with particularly good coverage, the smallest volcano measured just 421 meters high, a fairly small nodule as far as volcanoes go on the bumpy seafloor.

Most were taller than 700 meters, with some extending up to 2,500 meters above the seabed. Using these well-surveyed volcanoes as a guide, the researchers then estimated the shape and size of the other mounts they located.

Researchers not involved in the work say the findings could deepen our understanding of plate tectonics, volcanism, and the movements of ocean currents and marine life, in vast areas of the ocean that have gone unmapped for so long.

Guiding nutrient-rich waters up from the deep, seamounts are havens for marine life traversing the desert-like oceans. Their steep slopes also meddle with ocean currents that move heat around the globe. And buried in their geology, researchers expect to find clues on plate tectonics and magmatism, along with prized rare-earth minerals.

"Due to the impact that seamounts have on the ocean and ecosystems, they are important features to study, map, and classify," Gevorgian and colleagues write in their published paper.

Despite this massive update to the number of known seamounts, the researchers think there could be thousands more still waiting to be uncovered. In 2011, they estimated there could be up to 55,000 undersea peaks globally – a figure that might need revising based on the new numbers.

"Our study definitely helped make progress in the global seamount catalog, but improvements in the data resolution can help us find more," Gevorgian told Newsweek.

Missions are already underway to help achieve this, but detecting smaller seamounts isn't easy: They can be obscured by ocean sediments piled over them, or by nearby seabed features and turbulent ocean currents that may scramble the subtle gravitational differences that satellites are designed to pick up.

The study has been published in Earth and Space Science.