A strong response to certain smells could help doctors determine the best treatment for patients in comas, vegetative states, or minimally conscious states, conditions collectively known as disorders of consciousness (DoC).

Identifying which condition a patient has can be tricky, however. We've used sounds or images to test DoC, and a new study shows that smells can help, too. With the right refinement of this research, these conditions could be identified through carefully selected odors placed under a patient's nose.

"Olfactory responses should be considered signs of consciousness," write the researchers in their published paper. "The olfactory response may help in the assessment of consciousness and may contribute to therapeutic orientation."

Tests involving 28 patients in various levels of consciousness were carried out by a team from the Southern Medical University in China. Different odors, including vanillin and decanoic acid, were tried in the experiments, while electroencephalogram (EEG) scans were used to monitor brain activity.

A higher level of consciousness tended to mean more of a response to the smells.

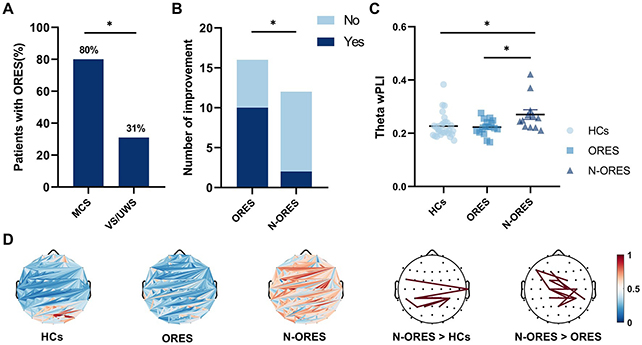

Indeed, three months later, of the 16 patients who responded to odors, 10 had recovered consciousness. That compares to just 2 out of the 12 patients from the group where there was no response to the olfactory stimuli.

Even in that latter group, there were some interesting brain patterns, though: specifically, higher theta functional connectivity in the brain, which is associated with drowsiness and relaxation, and lower alpha and beta connectivity relative to healthy controls, brain waves linked to alertness, and active thinking.

This was only observed with the vanillin scent, however – and the researchers think there might be some kind of relationship between the pleasantness of the smell and how likely people with DoCs are to respond to it.

"Theta connectivity may be a neural correlation with olfactory consciousness in patients with DoC, which could help in the assessment of consciousness and contribute to therapeutic strategies," write the researchers.

Our olfactory systems work differently from other senses in not involving the thalamus part of the brain, a sort of relay station linked to consciousness. Smells have a more direct connection to the forebrain, which might be helpful in this context, the researchers say.

All this plays into our understanding of consciousness, the brain's reaction to smell, and how the two may be linked. However, there's much more work to do on larger groups of people and a broader range of smells first.

One next step is to figure out why this link exists. It's possible that with a lower level of consciousness, we actually lose our ability to process smells normally, the researchers suggest – but for now, we're not sure.

"Future research should follow the recovery of consciousness after olfactory assessments over a longer period," write the researchers.

"Future research should also include time-frequency indicators or olfactory evoked potentials, which would add to our understanding of olfactory processing."

The research has been published in Frontiers in Neuroscience.