For the first time, scientists have found evidence that female crocodiles can lay eggs without mating, using a strange reproductive strategy that may have its evolutionary roots in the age of the dinosaurs.

In 2018, a lone female American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) held in captivity for 16 years laid a clutch of eggs, with one containing a discernable fetus, a female like her mother.

Genetic analyses from a team of US scientists have now revealed the crocodile produced the eggs without any input from a male mate, in a process called parthenogenesis, more commonly known as 'virgin births'.

Although the eggs didn't hatch, it's an astounding discovery in a new animal kingdom branch that shows how far back this unusual reproductive strategy goes.

Now that virgin births have been documented in crocodiles and birds, the findings suggest that their ancient forebears, the dinosaurs, might have shared these miraculous reproductive abilities.

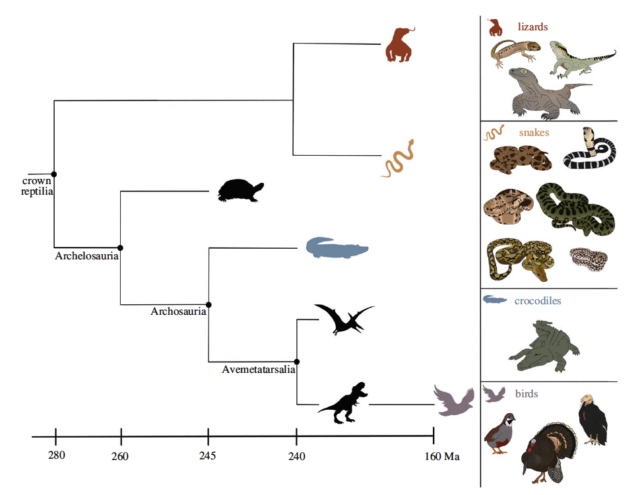

Crocodiles and birds are the living members of a clade of reptiles called archosaurs that, once upon a time, if we retrace its branches, also included dinosaurs and flying reptiles.

"[T]his discovery offers tantalizing insights into the possible reproductive capabilities of the extinct archosaurian relatives of crocodilians and birds, notably members of Pterosauria and Dinosauria," writes the team of researchers led by evolutionary biologist Warren Booth from Virginia Tech.

Parthenogenesis is a form of asexual reproduction where female animals who would typically need a male's sperm to reproduce can do so without mating. Rather than storing sperm for years, as reptiles can do, in a pinch, females can fuse two of their cells to make a viable embryo that has only one parent.

Once considered rare, scientists slowly realized that parthenogenesis was more common in vertebrate animals than they first thought.

Plants and invertebrates have been at it for a while, but it took some time for researchers to realize female vertebrates could produce offspring from eggs not fertilized by male sperm.

Virgin births have since been observed in more than 80 vertebrate species including in lizards, snakes, sharks, and rays but mostly in captive animals – and never before documented outside those vertebrate lineages until now.

Sure enough, when scientists looked closer still, they began to find examples of facultative parthenogenesis in wild animals, following a hunch that it could be a survival strategy that females adopt when they can't find a male mate, especially in sparse populations on the verge of extinction.

However, more recent findings from captive-bred Californian condors have suggested that these critically endangered birds can reproduce independently even when females are in regular contact with perfectly fertile males, so go figure.

As for the crocodile, genetic analysis of the stillborn fetus compared to its mother showed they shared practically identical genotypes.

This clone-like similarity suggests terminal fusion automixis was the reproductive mechanism in this example of parthenogenesis, just like what has been observed in studies of birds, snakes, and lizards.

This, Booth and colleagues write, points to parthenogenesis being a trait "likely possessed by a distant common ancestor of these lineages". However, more research is required to "fully test the evolutionary distribution and dynamics of [facultative parthenogenesis] across deeper evolutionary time."

Terminal fusion automixis is one way virgin births occur: a female fuses an egg – which contains half of her chromosomes – with another type of haploid cell called polar bodies that are left over from the ovaries' usual production of eggs. It involves a slight reshuffling of genetic material to fill in the blanks of the missing sperm, and the resulting offspring are near-clones of their mothers.

So while it might be a way females can reproduce alone when mates are few and far between, it's not a sustainable way of producing offspring because they lack the genetic diversity two parents bring.

And although the eggs didn't hatch in this instance, the researchers say that doesn't rule out the possibility that crocodiles use parthenogenesis to produce viable offspring. Rates of parthenogenetic eggs hatching in other species can be as low as 3 percent.

The study has been published in Biology Letters.