A muscle relaxant drug, discovered 150 years ago, may have a new role to play in modern medicine.

New research suggests that the drug, called papaverine, could give a much-needed boost to radiation therapy, increasing its impact on cancerous cells in hard-to-reach areas.

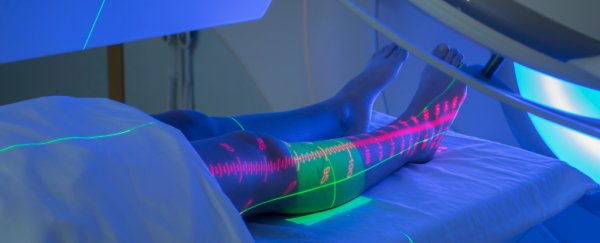

Radiation therapy kills malignant cells by damaging their DNA. While this approach can be quite effective, it has a huge downside: it does not work as well on tissue that is starved of oxygen.

Unfortunately, oxygen deprivation, or hypoxia, is common in cancerous cells. So radiation therapy struggles to target the very areas where it is most desperately needed.

"We know that hypoxia limits the effectiveness of radiation therapy, and that's a serious clinical problem because more than half of all people with cancer receive radiation therapy at some point in their care," says lead author Nicholas Denko, a researcher in tumour microenvironments and metabolism at Ohio State University.

Overcoming this barrier, or eliminating hypoxia, has been a six-decade-long quest for researchers. And now, it seems like Denko and his team have an intriguing new lead.

Cancerous cells need to consume high levels of oxygen to maintain their rapid growth. At times, their voracious appetite can outpace the available blood supply.

As hypoxia sets in, these cancer cells are shielded from the full force of chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

"If malignant cells in hypoxic areas of a tumour survive radiation therapy, they can become a source of tumour recurrence," Denko says.

"It's critical that we find ways to overcome this form of treatment resistance."

While most previous studies have tried to solve this problem by delivering more oxygen to the tumour, there have been few successes – mostly because tumours grow so fast, they end up with fewer blood vessels to even deliver oxygenated blood.

So Denko and his team decided to mix things up.

"We took the opposite approach," he explains. "Rather than attempting to increase oxygen supply, we reduced the oxygen demand."

That's where a 150-year-old muscle relaxant comes into the picture.

Papaverine works by inhibiting the respiration of mitochondria, the part of our cells - including cancer cells - that consumes oxygen and creates energy.

By reducing the amount of oxygen these cancer cells are consuming, the drug was found to reduce hypoxia and improve the efficacy of radiation on model tumours.

Even better, the researchers found that the drug has no impact on well-oxygenated normal tissue – it just targets hypoxic tissue.

"We found that one dose of papaverine prior to radiation therapy reduces mitochondrial respiration, alleviates hypoxia, and greatly enhances the responses of model tumours to radiation," says Denko.

Denko and his team were also able to show that certain modifications to the papaverine molecule might improve its safety and decrease the side-effects that go along with the drug.

These are both important steps when moving towards a clinically-approved drug.

Alongside the newly published research is a commentary from the journal itself, calling the study "a potential landmark" in the quest for improved radiotherapy.

The study has been published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.