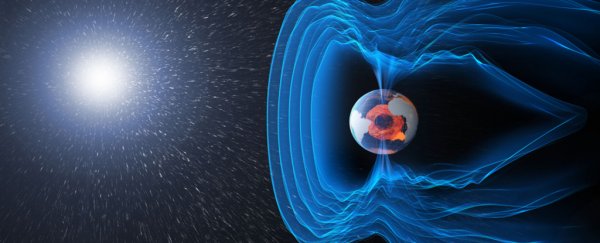

Our planet's protective shell isn't quite what it used to be. Over the past two centuries its magnetic strength has taken a nosedive, and nobody has the foggiest idea why.

At the same time, a concerning soft-spot in the field called the South Atlantic Anomaly has blistered over the Atlantic ocean, and has already proven problematic for delicate circuitry on orbital satellites.

Both of these troubling observations fuel concerns that we might be seeing signs of an imminent reconfiguration that would turn the compass points all topsy-turvy in what's known as a magnetic pole reversal.

But researchers behind a new investigation modelling the planet's magnetic field in the recent past warn that we shouldn't be too hasty in assuming that's going to happen.

"Based on similarities with the recreated anomalies, we predict that the South Atlantic Anomaly will probably disappear within the next 300 years, and that Earth is not heading towards a polarity reversal," says geologist Andreas Nilsson from Lund University in Sweden.

Not any time soon, at least. So for now we can breathe easy.

Still, if our geological history is anything to go by, it's likely the flowing lines of our planetary magnetic field will eventually point the other way around.

What such a reversal would mean for humanity isn't clear. The last time such a monumental event occurred, a mere 42,000 years ago, life on Earth seemed to go through a rough period as a rain of high-speed charged particles ripped through our atmosphere.

Whether we humans noticed – perhaps responding by spending a bit more time sheltering – is a matter of speculation.

However, given today's reliance on electronic technology that could be vulnerable without the protection of a magnetic umbrella, even the most rapid of field reversals in the foreseeable future would leave us exposed.

So geologists are keen to know which wiggles, wobbles, and wanderings in the field herald catastrophe, and which imply business as usual.

Much of what we know of the magnetic field's history comes from the way its orientation forces particles in molten materials to line up before being locked in place as they solidify. Digging through layers of mineralized arrows provides a fairly clear record of which way the compass pointed throughout the millennia.

Similarly, pottery artifacts from archaeological sites can also provide a snapshot of the field in more recent times, capturing its direction in clay before firing.

In the new study, researchers from Lund University and Oregon State University reconstructed a detailed timeline of our planet's magnetic shell stretching back towards the last ice age, by analyzing samples of volcanic rocks, sediments, and artifacts from around the world.

"We have mapped changes in the Earth's magnetic field over the past 9,000 years, and anomalies like the one in the South Atlantic are probably recurring phenomena linked to corresponding variations in the strength of the Earth's magnetic field," says Nilsson.

With thousands of years of perspective, it quickly becomes clear the South Atlantic soft-spot isn't completely out of the ordinary. Starting around 1600 BCE, a similar geological change took place, lasting some 1,300 years before evening out once more.

Assuming the same basic mechanics are at work, it's likely the current patch of weakening will soon regain strength and fade away without ending in global reconfiguration. It's even likely the magnetic field as a whole will bounce back to a vigor we haven't seen since the early 19th century.

This isn't proof against a reversal occurring soon, however – just new evidence suggesting we shouldn't interpret present anomalies of diminishing strength as strong signs of a polar flip.

In some ways, that's good news. But it leaves us in the dark on exactly what such a massive geological process will look like in the scale of a human lifetime.

Having detailed records like this one goes a long way towards building a clearer picture, so maybe if the worst happens, we'll be prepared for it.

This research was published in PNAS.