Seven new funnel web spider species have been found emerging in caves in Israel, and they're all in various stages of losing their vision.

In Charles Darwin's famous example of adaptation, a population of finches split apart on different islands gradually drifted from their shared ancestral form, to the point they came to represent distinct species.

This early observation recognized isolation as a key ingredient for organisms to change enough to speciate.

But as this latest cave discovery shows, vast stretches of water are just one way populations can be separated.

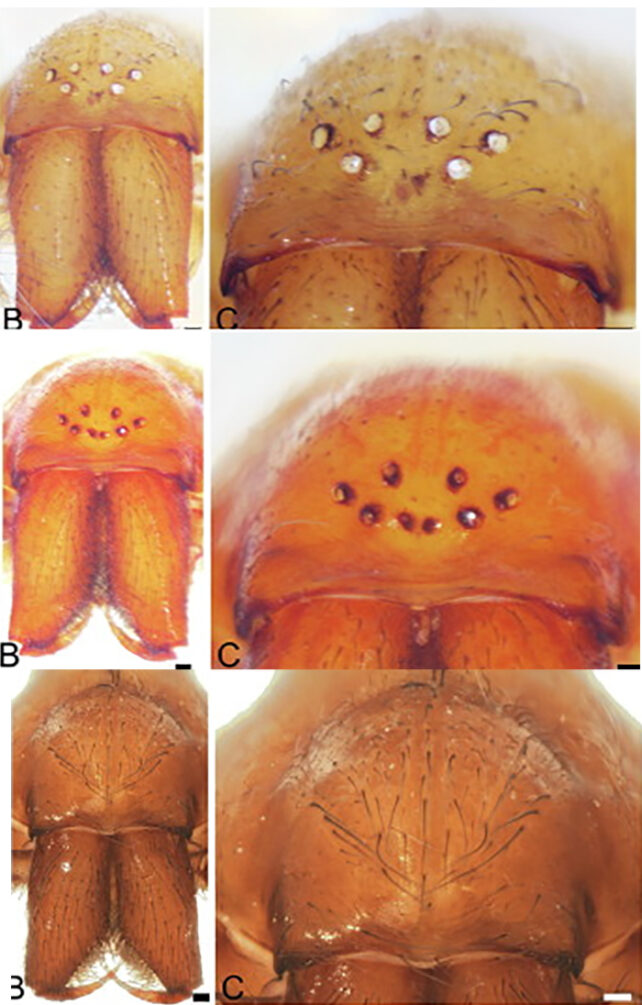

"In this study, we sought to understand the evolutionary relationships between funnel web spiders with normal eyes that are found at the cave entrance, with those that are further in the cave and are pigmentless, eye-reduced, and even completely blind," explains ecologist Shlomi Aharon from the The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI).

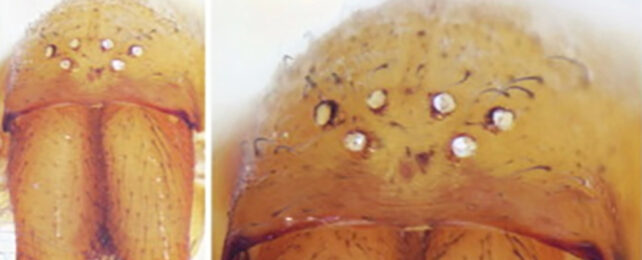

Aharon and colleagues found species of Tegenaria funnel web spiders in 30 caves. Twenty-six of these were cave-preferring species that still relied on some outside conditions like light (troglophiles) and they lived at the entrances and twilight zones of the caves. Meanwhile, 14 other species were found to be obligate cave dwellers (troglobites), who only inhabit the twilight or dark zones.

Seven of these troglobite species were new to science, five of them with reduced eyes and two completely blind.

"Among the spiders we found, five were unique to different caves, and the two other species were found in several caves in the Galilee and in caves situated at the Ofra karst field, which is now under threat due to construction plans," explains HUJI ecologist Efrat Gavish-Regev.

The researchers analyzed the spiders' DNA to track their history across the landscape.

Those spiders that adapted to the unique cave conditions can no longer thrive in the world beyond these dark, sheltered crevices. This means there was very little if any gene flow between cave systems, even when each population sits relatively close to one another.

"One of the surprising findings in the study show that the new species are evolutionarily closer to species from caves in Mediterranean areas in southern Europe, than to species living in close proximity to them at cave entrances in Israel," says Gavish-Regev.

The genetic trail suggests a single Tegenaria species swept through the area and eventually ventured deeper into the caves. By removing the need for functional eyes, the new environment molded their traits, selecting for offspring that didn't waste energy on unnecessary visual systems. This happened independently across the different cave systems – a process called convergent evolution – resulting in distinct species all losing their eyes after they went separate ways.

Then the original species became locally extinct outside of the caves, before other related species moved in on the outside.

The team suspects the extinction event was a result of climate change around 5 million years ago, during the beginning of the Pliocene when seas rose to present levels.

"We are currently witnessing the effects of climate change on many habitats, which obliges us to consider, maintain and promote programs that include the preservation of underground habitats – many of which are at immediate risk," concludes Hawlena.

"We must protect Israel's unique nature, preserve its underground systems for the future and further explore the processes that created these systems in the country."

This research was published in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.