A car-size asteroid flew within about 1,830 miles (2,950 kilometers) of Earth on Sunday.

That's a remarkably close shave – the closest ever recorded, in fact, according to asteroid trackers and a catalogue compiled by Sormano Astronomical Observatory in Italy.

Because of its size, the space rock most likely wouldn't have posed any danger to people on the ground had it struck our planet. But the close call is worrisome nonetheless, since astronomers had no idea the asteroid existed until after it passed by.

"The asteroid approached undetected from the direction of the Sun," Paul Chodas, the director of NASA's Centre for Near Earth Object Studies, told Business Insider.

"We didn't see it coming."

Instead, the Palomar Observatory in California first detected the space rock about six hours after it flew by Earth.

Chodas confirmed the record-breaking nature of the event: "Yesterday's close approach is closest on record, if you discount a few known asteroids that have actually impacted our planet," he said.

NASA knows about only a fraction of near-Earth objects (NEOs) like this one. Many do not cross any telescope's line of sight, and several potentially dangerous asteroids have snuck up on scientists in recent years.

If the wrong one slipped through the gaps in our NEO-surveillance systems, it could kill tens of thousands of people.

2020 QG flew over the Southern Hemisphere

This recent near-Earth asteroid was initially called ZTF0DxQ but is now formally known to astronomers as 2020 QG. Business Insider first learned about it from Tony Dunn, the creator of the website orbitsimulator.com.

"Newly-discovered asteroid ZTF0DxQ passed less than 1/4 Earth diameter yesterday, making it the closest-known flyby that didn't hit our planet," Dunn tweeted on Monday.

He shared the animation below, republished here with permission.

The sped-up simulation shows the approximate orbital path of 2020 QG as it careened by at a speed of about 7.7 miles per second (12.4 kilometers per second) or about 27,600 mph (44,000 km/h).

Early observations suggest the space rock flew over the Southern Hemisphere just after 4 a.m. Universal Time (midnight ET) on Sunday.

The animation above shows 2020 QG flying over the Southern Ocean near Antarctica.

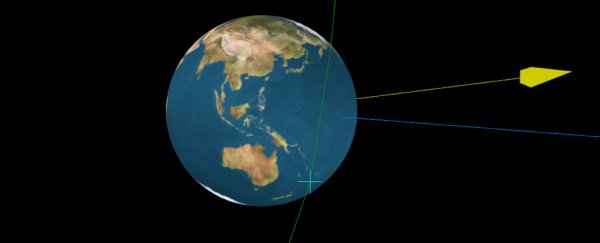

However, the International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Centre calculated a slightly different trajectory. The group's rendering (shown below), suggests the asteroid flew over the Pacific Ocean hundreds of miles east of Australia.

(Minor Planet Centre/International Astronomical Union)

(Minor Planet Centre/International Astronomical Union)

Above: A diagram of asteroid 2020 QG flying past Earth on August 16. The yellow arrow shows the direction of the sun, blue shows Earth's direction, and the green hatches show the asteroid's location every 30 minutes.

Not dangerous, but definitely not welcome

As far as space rocks go, 2020 QG wasn't too dangerous.

Telescope observations suggest the object is between 6 feet (2 meters) and 18 feet (5.5 meters) wide – somewhere between the size of a small car and an extended-cab pickup truck. But even if it was on the largest end of that spectrum and made of dense iron (most asteroids are rocky), only small pieces of such an asteroid may have reached the ground, according to the "Impact Earth" simulator from Purdue University and Imperial College London.

Such an asteroid would have exploded in the atmosphere, creating a brilliant fireball and unleashing an airburst equivalent to detonating a couple dozen kilotons of TNT.

That's about the same as one of the atomic bombs the US dropped on Japan in 1945. But the airburst would have happened about 2 or 3 miles above the ground, so it wouldn't have sounded any louder than heavy traffic to people on the ground.

This doesn't make the asteroid's discovery much less unnerving, though – it does not take a huge space rock to create a big problem.

Take, for example, the roughly 66-foot-wide (20-metre) asteroid that exploded without warning over Chelyabinsk, Russia, in February 2013. That space rock created a superbolide event, unleashing an airburst equivalent to 500 kilotons of TNT – about 30 Hiroshima nuclear bombs' worth of energy.

The explosion, which began about 12 miles (20 kilometers) above Earth, triggered a blast wave that shattered windows in six Russian cities and injured about 1,500 people.

And in July 2019, a 427-foot (130-metre) asteroid called 2019 OK passed within 45,000 miles (72,400 kilometers) of our planet, or less than 20 percent of the distance between Earth and the moon.

Astronomers detected that rock less than a week before its closest approach, leading one scientist to tell The Washington Post that the asteroid essentially appeared "out of nowhere."

In an unlikely direct hit to a city, such a wayward space rock might kill tens of thousands of people.

NASA is actively scanning the skies for such threats, as Congress has required it to do since 2005. However, the agency is mandated to detect only 90 percent of "city killer" space rocks larger than about 460 feet (140 meters) in diameter.

In May 2019, NASA said it had found less than half of the estimated 25,000 objects of that size or larger. And of course, that doesn't count smaller rocks such as the Chelyabinsk and 2019 OK asteroids.

Objects that come from the direction of the sun, meanwhile – like 2020 QG – are notoriously difficult to spot.

"There's not much we can do about detecting inbound asteroids coming from the sunward direction, as asteroids are detected using optical telescopes only (like ZTF), and we can only search for them in the night sky," Chodas said.

"The idea is that we discover them on one of their prior passages by our planet, and then make predictions years and decades in advance to see whether they have any possibility of impacting."

NASA has a plan to address these gaps in its asteroid-hunting program. The agency is in the early stages of developing a space telescope that could detect asteroids and comets coming from the sun's direction. NASA's 2020 budget allotted nearly US$36 million for that telescope, called the Near-Earth Object Surveillance Mission. If funding continues, it could launch as early as 2025.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: