In a ghastly vision of a future cut off from sunlight, the machine overlords in the Matrix movie series turned to sleeping human bodies as sources of electricity. If they'd had sunlight, algae would undoubtedly have been the better choice.

Engineers from the University of Cambridge in the UK have run a microprocessor for more than six months using nothing more than the current generated by a common species of cyanobacteria. The method is intended to provide power for vast swarms of electronic devices.

"The growing Internet of Things needs an increasing amount of power, and we think this will have to come from systems that can generate energy, rather than simply store it like batteries," says Christopher Howe, a biochemist and (we assume) non-mechanical human.

Unlike the side of the internet we use to tweet and share TikTok clips, the Internet of Things connects less opinionated objects such as washing machines, coffee makers, vehicles, and remote environmental sensors.

In some cases, these devices operate far from a power grid. Often they're so remote, or in such inconvenient spots, there's no easy way to pop in a fresh battery when they run down, or fix their power source should it degrade or break.

For tech that runs on a mere flicker of current, the solution is to simply soak up energy from the environment, capturing movements, carbon, light, or even waste heat and using it to push out a voltage.

Photovoltaic cells (solar power) are an obvious solution in today's world, given the rapid progress that's been made in recent years in squeezing more power from every ray of sunshine.

If you want power at night, though, you'll need to add a battery to your device, which not only adds mass, but requires a mix of potentially costly and even toxic substances.

Creating a 'living' power source that converts material in the environment, such as methane, makes for a greener, simpler power cell that won't weaken as the Sun sets. On the other hand, they will run out of juice the moment their food supply runs out.

Algae could be the solution that provides a middle-ground option, acting as a solar cell and living battery to provide a reliable current without a need for nutrient top-ups. Already being explored as a source of energy for larger operations, algae could provide power for countless tiny devices as well.

"Our photosynthetic device doesn't run down the way a battery does because it's continually using light as the energy source," says Howe.

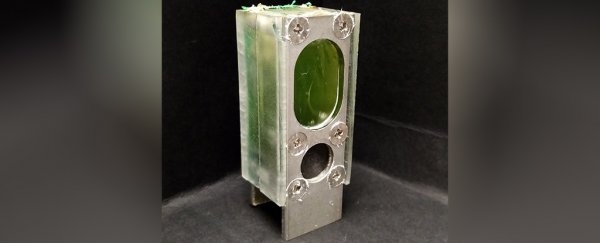

Their bio-photovoltaic system uses aluminum wool for an anode, primarily because it's relatively easy to recycle and less of a problem for the environment compared with many other options. It also provided the team with an opportunity to investigate how living systems interact with power-generating aluminum-air batteries.

The 'bio' part of the cell was a strain of freshwater cyanobacteria called Synechocystis, selected for its ubiquity and the fact it's been studied so extensively.

Under perfect laboratory conditions, a AA-battery-sized version of the cell managed to produce just over four microwatts per square centimeter. Even when the lights were out, the algae continued to break down food reserves to generate a smaller but still appreciable current.

That might not sound like much, but when you only need a tiny bit of power to operate, algae-power could be just the ticket.

A programmable 32-bit reduced-instruction-set processor commonly used in microcontrollers was given a set of sums to chew on for a 45 minute session, followed by a 15 minute rest.

Left in the ambient light of the laboratory, the processor ran through this same task for more than six months, demonstrating simple algae-based batteries are more than capable of running rudimentary computers.

"We were impressed by how consistently the system worked over a long period of time – we thought it might stop after a few weeks but it just kept going," says biochemist Paolo Bombelli.

Given the rate at which we're finding new ways to build electronics into everyday items, it's clear we can't keep churning out lithium-ion batteries to power them all.

And frankly, using sleeping human bodies to power vast swarms of computers is just plain overkill. Isn't that right, machines?

This research was published in Energy & Environmental Science.