Throughout its life, our planet has been pummelled by countless asteroids and comets - even more so than the crater-ridden Moon. Today, thanks to Earth's continually changing surface, there are remarkably few scars left to tell the tale.

Australia's relatively stable and ancient landscape not only harbours potentially the largest of those blemishes, scientists now think it also contains the oldest… by a long, long shot.

"When the age came back at 2.229 billion years, that blew our hair back," geochemist Aaron Cavosie from Curtin University in Australia told ScienceAlert.

"We've known about this crater for almost 20 years, but nobody realised it was the oldest until now."

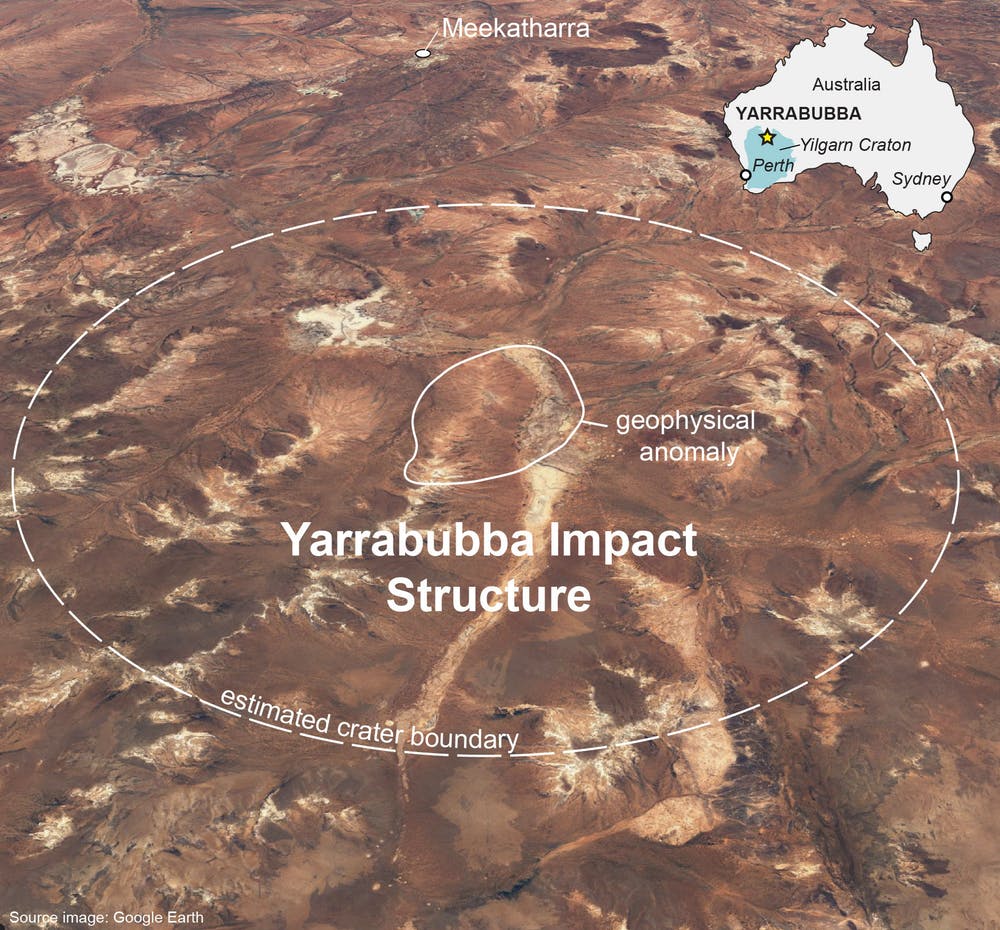

The Yarrabubba crater is a massive indent in the Western Australian outback, roughly 70 kilometres wide (44 miles).

Location of the crater. (The Conversation)

Location of the crater. (The Conversation)

The impact was always assumed to be ancient, but modern geological dating suggests this particular case is over 200 million years older than the next oldest impact. If humans represent the tip of your fingernail on the timeline of your outstretched arms, this would place the Yarrabubba collision smack dab in the centre of your chest, roughly half the age of Earth.

We know this because when the meteorite hit, it sent a high-pressure shock wave through the area, rattling atoms and damaging minerals on a minute level.

"After the shock wave passes through rocks, they are compressed like a spring," Cavosie told ScienceAlert.

"When they release, the instantly heat up, to temperatures higher than that found in a volcano. This makes some rocks in the centre of impacts vaporise, while others just melt at high temperature, often over 2,000 degrees C (3,600 F). "

Uranium is steadily converted to lead at a known pace, but when these crystals are shocked and heated up, they are suddenly rid of all lead, re-setting the 'isotopic clock'.

Winding back the billions of years on this timeline is notoriously difficult, because it essentially requires a collection of tiny isotopic traces in the crystal structure of a grain no more than the width of a hair.

Luckily enough, Yarrabubba had just what the researchers were looking for.

"[The] crater was made right at the end of what's commonly referred to as the early Snowball Earth, a time when the atmosphere and oceans were evolving and becoming more oxygenated and when rocks deposited on many continents recorded glacial conditions," says earth and planetary scientist Chris Kirkland from Curtin University.

This means that when the meteorite hit Earth over 2 billion years ago, it may very well have collided with a continental ice sheet, kicking up huge amounts of rock, ash and dust - like a major volcanic eruption.

Running simulations, the authors calculate this situation would spread between 87 trillion and 5,000 trillion kilograms of water vapour into the atmosphere. Since water is an efficient greenhouse gas, this might have helped modify the climate and thaw the planet.

This is just a potential scenario; the exact climate conditions of this time are still under debate. Even still, the authors argue that considering Earth's atmosphere contained only a fraction of today's oxygen, "a possibility remains that the climatic forcing effects of H2O vapour released instantaneously into the atmosphere through a Yarrabubba-sized impact may have been globally significant."

Impact craters like this one are precious windows into Earth's past, and yet there are only about 190 of these structures in the world, some of which are hard to differentiate from tectonic deformation.

Palaeoclimate scientist Andrew Glikson told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation that while he considered the team's dating "excellent", in his opinion the oldest known impact structure was in Greenland 800 million years earlier, although there's currently fierce debate over whether this impact structure was actually made by a meteorite.

Regardless of the results of that debate, research on Yarrabubba shows that extremely old impact events may very well have affected our climate history on a large scale.

"These kinds of discoveries re-write pages in the history books, and inform us about the early evolution of Earth," Cavosie told ScienceAlert.

"That feeling never goes out of style."

The study was published in Nature Communications.