A new study pointing to reduced levels of a well-known chemical messenger in people with long COVID has landed on a pathway that unites several possible causes of the disabling condition.

Just like other researchers before them, University of Pennsylvania immunologist Andrea Wong and colleagues went in search of distinct biological changes that might explain the puzzling mix of up to 200 potential symptoms people with long COVID can experience.

Research has come a long way since the early days of the pandemic in deciphering the possible causes of long COVID, which can last months or even years after an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection passes.

But this growing body of research also presents a somewhat messy picture of overlapping, underlying causes: increased blood clotting, a lingering virus, persistent inflammation, and a dysfunctional nervous system are just some of the working theories attempting to explain long COVID's development.

The findings of this new study suggest four of those mechanisms might be interconnected, and could explain the cognitive difficulties and memory loss people with long COVID report. Not only that, the study could point the way toward possible treatments if the results are replicated in larger cohorts.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 58 long COVID patients, and found a few differences that separated them from 30 people who fully recovered.

Those with long COVID had depleted levels of serotonin, a chemical messenger best known for its role in boosting mood, amongst other functions relating to memory, cognition, and sleep. Long haulers also shed remnants of viral particles in their stools.

Using a combination of animal models and organoid cultures, the team then pieced together a possible pathway linking a lack of serotonin in the gut, where most serotonin is usually produced, to its effects in the brain.

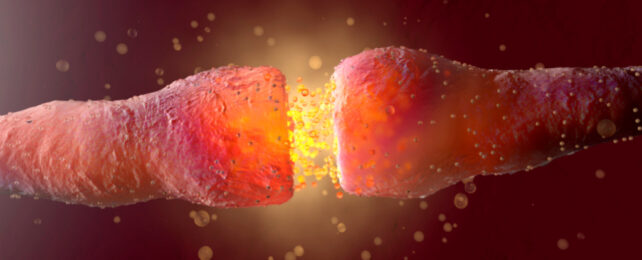

The connection they propose goes like this: lingering viral material could trigger the body's immune system to pump out interferons, a group of signaling proteins involved in anti-viral defenses.

This drives inflammation, which limits the absorption of tryptophan, an amino acid used to make serotonin, in the gut.

Persistent inflammation also messes with platelets, blood cells involved in blood clotting that also carry serotonin around the body.

Less circulating serotonin then impairs the activity of the vagus nerve, the body's superhighway sending signals between the brain, gut, and other organs.

"Our findings suggest that several of the current hypotheses for the pathophysiology of long COVID (viral reservoir, persistent inflammation, hypercoagulability, vagus nerve dysfunction) might be linked by a single pathway that is connected by serotonin reduction," Maayan Levy, University of Pennsylvania microbiologist and senior author of the study, explained on social media.

In mice, low serotonin levels and reduced vagus nerve activity from a viral infection resulted in the animals performing worse on memory tests.

Yet remarkably, those memory impairments – which resemble but obviously don't replicate the cognitive troubles of long haulers – could be prevented when serotonin levels were restored.

More human studies are needed to test those suggestions. Future research also needs to resolve why some people in a second cohort of long COVID patients, possibly with milder symptoms, didn't have low serotonin levels.

"We hope that our discovery will inspire clinical studies that use these insights to develop new tools for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of long COVID," Levy added. "They are so urgently needed."

The study has been published in Cell.