High cholesterol is becoming an all-too common health problem, now affecting almost 2 in 5 adults in the US. Now a new vaccine currently in development promises to effectively and affordably lower levels of 'bad' cholesterol in the body.

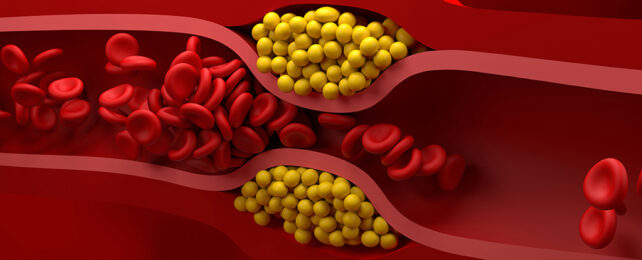

This bad cholesterol – in the form of low-density lipoproteins or LDLs – is the type that can cause dangerous blockages in the arteries, reducing oxygen flow to the heart or causing blood clots that can lead to a stroke.

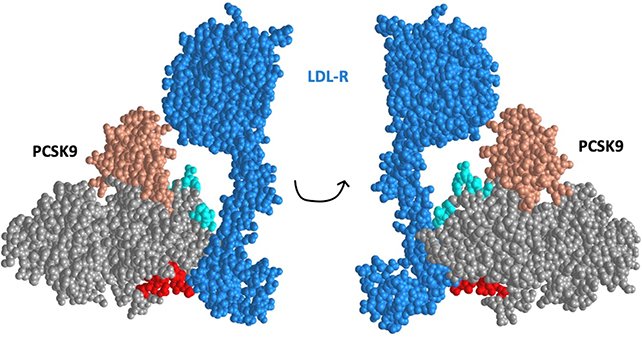

In tests on mice and monkeys, a team led by researchers from the University of New Mexico and the University of California, Davis were able to reduce LDL levels by targeting a protein called proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), known to have an important relationship to LDLs.

"The vaccine is based on a non-infectious virus particle," says molecular geneticist Bryce Chackerian from the University of New Mexico.

"It is just the shell of a virus, and it turns out that we can use that shell of a virus to develop vaccines against all sorts of different things."

Special receptors on liver cells are responsible for keeping LDLs at a safe level, but an excess of PCSK9 can harm these receptors, meaning the receptors become less effective and there's more bad cholesterol floating around in the blood.

Genetics, diet, and various other factors can influence PCSK9 production in the body. Here, the combination of tiny bits of PCSK9 with the non-infectious virus particle meant that an immune system response was triggered, targeting and neutralizing the PCSK9 protein.

The vaccine developed by the researchers was shown to be able to reduce bad cholesterol by up to 30 percent. Though it's as effective as current PCSK9 inhibitors, it's a solution that could potentially cost much less.

"We are interested in trying to develop another approach that would be less expensive and more broadly applicable, not just in the United States, but also in places that don't have the resources to afford these very, very expensive therapies," says Chackerian.

We're still quite a long way off from getting a vaccine that can be used in human beings, but these are promising results, in a solution that would be more affordable than current options and last around a year per dose.

Already a decade in development, the next stage for the vaccine is trials in humans, though that will require further study and further financing – all of which will be worth it if it reduces the close to 18 million lives lost globally every year to cardiovascular disease.

"We hope to have a vaccine in people in the next 10 years," says Chackerian.

The research has been published in NPJ Vaccines.