Twenty years of satellite data show that a stretch of coastal desert extending south from Peru's north and into Chile is getting greener, but this is not good news.

"This is a warning sign, like the canary in the mine," cautions Cambridge University mathematician Hugo Lepage.

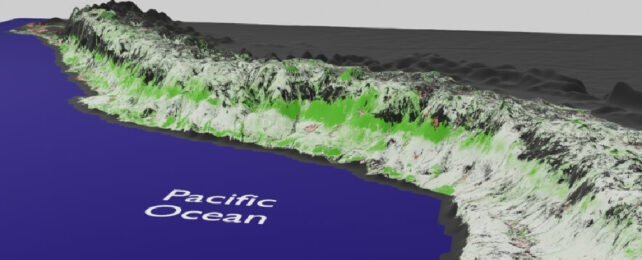

Scattered mist oases filled with unique vegetation, called lomas, pepper 2,800 kilometers of the arid coastline. Their only source of water is sea-generated fog. This region has an average rainfall of just 3 to 13 mm per year, with many years experiencing no rain at all, leaving it mostly entirely without vegetation.

Species found nowhere else in the world, such as wild tomatoes, the endangered Andean Condor, and the now domestically popular air plants (Tillandsia), call these green islands among the desert home.

These delicate ecosystems boom and bust with climatic cycles – sometimes disappearing completely for five to 10 years, but then increased rain during El Niño years also triggers stunning flowering periods.

But over the last couple of decades, satellite data reveal the lomas scattered amongst the long strip of foothills between the high Andes mountains and the vast ocean are growing. While this is a boon for the local flora and fauna, much of which is endangered, their grains likely mean trouble elsewhere.

The large extent of these changes will alter the area's limited resource distribution. Agricultural lands bringing irrigation are also spreading, adding more green to the region as well. This changing land use directly impacts the lomas, too. Meanwhile, other areas are unexpectedly browning.

"The Pacific slope provides water for two-thirds of the country, and this is where most of the food for Peru is coming from, too," explains Cambridge University geographer Eustace Barnes. "This rapid change in vegetation, and to water level and ecosystems, will inevitably have an impact on water and agricultural planning management."

It took Lepage and colleagues three years to verify their analysis, with numerous field trips to investigate some of the greening strips they had identified.

"First, the strip ascends as we look southward, going from 170–780 meters (557–2,559 feet) in northern Peru to 2,600–4,300 meters in the south of Peru", says Barnes. "This is counterintuitive, as we would expect the surface temperatures to drop both when moving south and ascending in altitude."

To their surprise, the greatest greening was occurring in what were previously the most arid zones.

"In northern Peru, the greening strip mostly lies in the climate zone corresponding to the hot arid desert," notes Lepage. "As we scan the strip going south, it ascends to lie mostly in the hot arid steppe and finally traverses to lie in the cold arid steppe. This did not match what we expected based on the climate in those regions."

While the researchers can't yet rule out that the increased greening isn't part of some longer regional climatic cycle that the 20 years of data haven't captured, the trends are generally in line with changing precipitation cycles driven by global CO2 concentrations over this period.

The team explains that the extra greening's relationship to land temperatures isn't as straightforward and requires further investigation.

"There is nothing we can do to stop changes at such a large scale. But knowing about it will help to plan better for the future," concludes Lepage.

This research was published in MDPI Remote Sensing.