Space is full of punctuation.

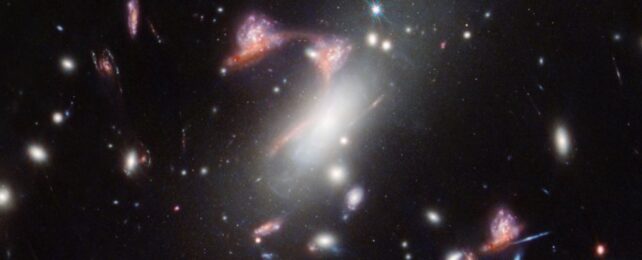

Look carefully, and you'll see periods, colons, ellipses, even commas. Complex symbols are slightly more elusive, but the JWST has just spotted one in the wild. There, in space-time warped and stretched by gravity, the light of a distant galaxy is contorted into the shape of a perfect, giant cosmic question mark.

Its resemblance to human language is a coincidence, of course, (although it's not the first question mark JWST has spotted in deep space). But the appearance of this particular object is due to a quirk of perspective, alignment, and physics known as a gravitational lens that can help us learn more about the Universe.

"We know of only three or four occurrences of similar gravitational lens configurations in the observable universe," says astronomer Guillaume Desprez of Saint Mary's University in Canada, "which makes this find exciting, as it demonstrates the power of Webb and suggests maybe now we will find more of these."

Space-time – the fabric of the Universe – isn't smooth and uniform. Massive objects cause it to stretch and warp, like putting a heavy object on a trampoline. Massive galaxies and galaxy clusters do something similar to space-time; any light traveling through that space-time does so along a stretched and curving path.

For us as observers here on Earth, seeing that distant light, the result is smearing, warping, multiplication, and magnification.

It's quite interesting to look at, and benefits science, too. It's a bit like a cosmic magnifying glass that allows us to see more details in distant galaxies than we would otherwise be able to, although scientists usually have to reverse the effects of the warp to get useful data.

This is what we're looking at here, but it's a particularly rare kind of lens called a hyperbolic umbilic gravitational lens. Behind a galaxy cluster called MACS-J0417.5-1154, in distant space, two galaxies have been caught interacting. This is what causes the question mark shape.

Because of the way the light from these galaxies has warped, five distinct, separate images of the pair reach us here on Earth. Four of those make up the curve of the question mark, with smears of warped light connecting them; the question mark's dot is a second, unrelated galaxy just hanging about in the right place at the right time.

Astronomers imaged the region using both JWST and Hubble, and were able to determine that the Question Mark Pair, as the two galaxies are now being called, are at the same distance away from us, both emitting light that has traveled 7.2 billion years to reach us.

This confirms that the galaxies are, indeed, interacting with each other. Both are also starting to bloom with star formation as their gravitational interaction causes their star-forming clouds of dust to smoosh together, buckle, and collapse into baby stars.

"Knowing when, where, and how star formation occurs within galaxies is crucial to understanding how galaxies have evolved over the history of the universe," says astronomer Vicente Estrada-Carpenter of Saint Mary's University.

"Both galaxies in the Question Mark Pair show active star formation in several compact regions, likely a result of gas from the two galaxies colliding. However, neither galaxy's shape appears too disrupted, so we are probably seeing the beginning of their interaction with each other."

Although gravitational lenses aren't shockingly rare, their quality varies, and we can't always extract useful information from them. An observation like the Question Mark Pair is a rare glimpse, not just into the history of the Universe, but our Milky Way's own weird history of violence.

"This is just cool looking. Amazing images like this are why I got into astronomy when I was young," says astronomer Marcin Sawicki of Saint Mary's University.

"These galaxies, seen billions of years ago when star formation was at its peak, are similar to the mass that the Milky Way galaxy would have been at that time. Webb is allowing us to study what the teenage years of our own galaxy would have been like."

A review of the survey in which this observation appeared has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.