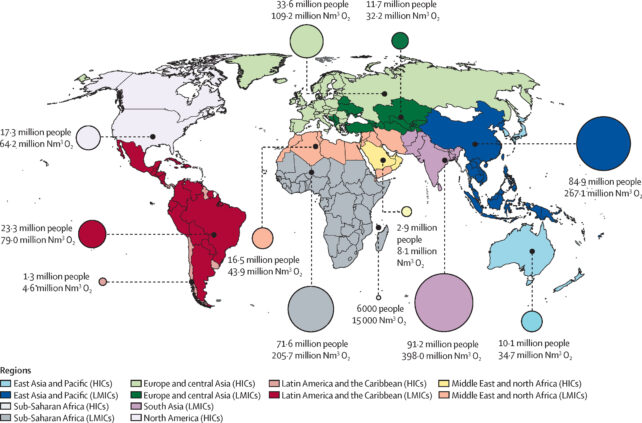

Every year around 374 million children and adults need access to medical oxygen to survive. This need is rising, but less than one in three people can obtain this life-saving treatment in non-wealthy countries.

In a new report, more than 30 researchers have laid out a plan to tackle this crisis.

"I carry the oxygen like a backpack, so I can go to school and get together with my friends, even exercise," explains a child living with chronic lung disease in Chile, quoted in the report. "[With oxygen] I can live a normal life with my illness."

Oxygen therapy is critical for people with emergency conditions and life-sustaining for those under anesthesia and people with chronic respiratory failure. We have been using it to save lives for at least 150 years now.

But getting it to all the people who need it has remained a global challenge.

"Oxygen is required at every level of the healthcare system for children and adults with a wide range of acute and chronic conditions," says Murdoch Children's Research Institute physician Hamish Graham, who is part of the commission tasked with the investigation into the medical oxygen crisis.

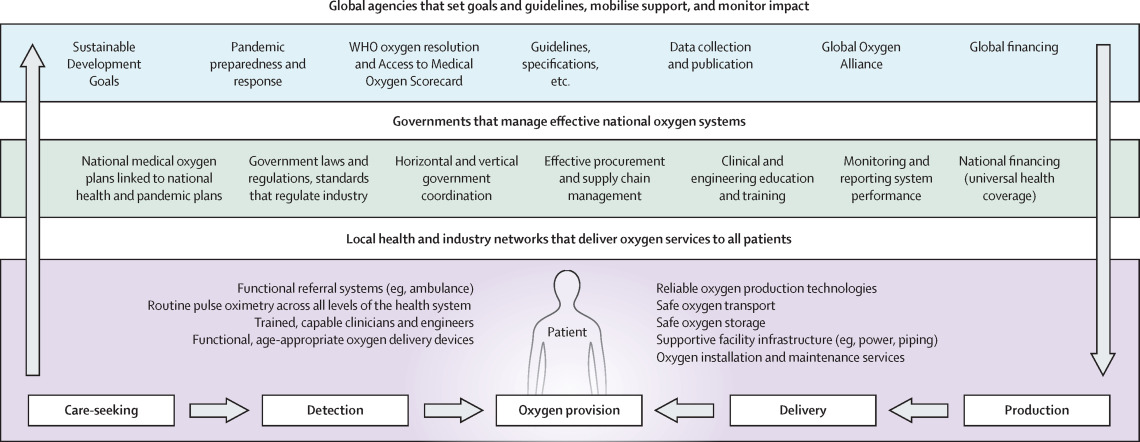

"Previous efforts… largely focused on the delivery of equipment to produce more oxygen, neglecting the supporting systems and people required to ensure it was distributed, maintained, and used safely and effectively."

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed many of these flaws, leading to the deaths of many loved ones.

"I don't want any future generations of doctors having to decide like God who lives and who dies, because that is what we had to do when there wasn't enough oxygen," says a physician in Ethiopia.

After an extensive analysis, the researchers laid out a plan for oxygen production, storage, and distribution systems that can be implemented in even the least wealthy nations.

They propose 52 recommendations for governments, the oxygen industry, global health advocates, academics and health professionals to work towards.

As well as increasing resources and improving cooperation between government and industry, the researchers identified that access to properly working pulse oximeters – a small device that measures oxygen levels in the blood – plays a huge role in ensuring medical oxygen gets where it is most needed on time.

What's more, studies reveal many pulse oximetry devices do not take accurate readings in people with darker skin colors.

"We urgently need to make high-quality, pulse oximeters more affordable and widely accessible," says Graham.

Currently in low- and middle-income countries, pulse oximeters are only available in 54 percent of general hospitals and 83 percent of tertiary hospitals. Even then, shortages and breakdowns are common.

"Right now, most of our hospitals are cemeteries for broken medical equipment," explains a physician in Sierra Leone.

This is exacerbated by a shortage of biomedical engineers – essential workers responsible for ensuring all the life saving equipment is working when needed.

"The number of available biomedical engineers was not adequate to handle the oxygen needs and maintenance of the electrical equipment," a physician in Ethiopia says.

Community education for both the use of medical oxygen and preventative health measures are also key pieces of the plan.

"He kept trying to pull off the oxygen mask," explains the wife of a patient that died from COVID-19 in the Philippines. "He could not tolerate it. It really disturbed him."

It's also critical, the report states, to promote preventative measures that reduce the demand for medical oxygen, including keeping up-to-date with immunizations, reducing smoking and pollution, promoting healthy diets, and mitigating climate change.

"I remember when I got to the emergency room, my saturation was 80 percent. I had a blackout in front of my eyes. I thought I would die," a young patient who experienced acute respiratory failure in Pakistan describes.

"I was sweating. I felt like there was no life in my hands or feet. I felt much better when I got on oxygen and my symptoms got better and I thought I would come out of it. It gave me hope."

The report was published in The Lancet Global Health.