To cram ever more computing power into your pocket, engineers need to come up with increasingly ingenious ways to add transistors to an already crowded space.

Unfortunately there's a limit to how small you can make a wire. But a twisted form of rare earth metal just might have what it takes to push the boundaries a little further.

A team of researchers funded by the US Army have discovered a way to turn twisted nanowires of one of the rarest of rare earth metals, tellurium, into a material with just the right properties that make it an ideal transistor at just a couple of nanometres across.

"This tellurium material is really unique," says Peide Ye, an electrical engineer from Purdue University.

"It builds a functional transistor with the potential to be the smallest in the world."

Transistors are the work horse of anything that computes information, using tiny changes in charge to prevent or allow larger currents to flow.

Typically made of semiconducting materials, they can be thought of as traffic intersections for electrons. A small voltage change in one place opens the gate for current to flow, serving as both a switch and an amplifier.

Combinations of open and closed switches are the physical units representing the binary language underpinning logic in computer operations. As such, the more you have in one spot, the more operations you can run.

Ever since the first chunky transistor was prototyped a little more than 70 years ago, a variety of methods and novel materials have led to regular downsizing of the transistor.

In fact the shrinking was so regular that co-founder of the computer giant Intel, George Moore, famously noted in 1965 that it would follow a trend of transistors doubling in density every two years.

Today, that trend has slowed considerably. For one thing, more transistors in one spot means more heat building up.

But there are also only so many ways you can shave atoms from a material and still have it function as a transistor. Which is where tellurium comes in.

Though not exactly a common element in Earth's crust, it's a semi-metal in high demand, finding a place in a variety of alloys to improve hardness and help it resist corrosion.

It also has properties of a semiconductor; carrying a current under some circumstances and acting as a resistor under others.

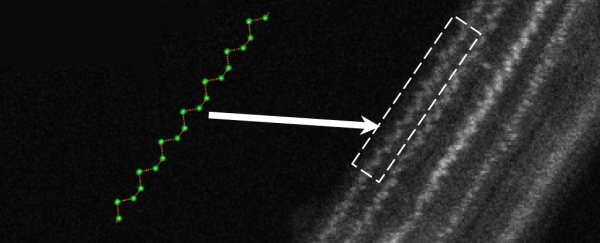

Curious about its characteristics on a nanoscale, engineers grew single-dimensional chains of the element and took a close look at them under an electron microscope. Surprisingly, the super-thin 'wire' wasn't exactly a neat line of atoms.

"Silicon atoms look straight, but these tellurium atoms are like a snake. This is a very original kind of structure," says Ye.

On closer inspection they worked out that the chain was made of pairs of tellurium atoms bonded strongly together, and then stacking into a crystal form pulled into a helix by weaker van der Waal forces.

Building any kind of electronics from a crinkly nanowire is just asking for trouble, so to give the material some structure the researchers went on the hunt for something to encapsulate it in.

The solution, they found, was a nanotube of boron nitride. Not only did the tellurium helix slip neatly inside, the tube acted as an insulator, ticking all the boxes that would make it suit life as a transistor.

Most importantly, the whole semiconducting wire was a mere 2 nanometres across, putting it in the same league as the 1 nanometre record set a few years ago.

Time will tell if the team can squeeze it down further with fewer chains, or even if it will function as expected in a circuit.

If it works as hoped, it could contribute to the next generation of miniaturised electronics, potentially halving the size of current cutting edge microchips.

"Next, the researchers will optimise the device to further improve its performance, and demonstrate a highly efficient functional electronic circuit using these tiny transistors, potentially through collaboration with ARL researchers," says Joe Qiu, program manager for the Army Research Office.

Even if the concept pans out, there's a variety of other challenges for shrinking technology to overcome before we'll find it in our pockets.

While tellurium isn't currently considered to be a scarce resource, in spite of its relative rarity, it could be in high demand in future electronics such as solar cells.

This research was published in Nature Electronics.