Archaeologists working near Stonehenge in the UK have discovered part of a giant ring of deep shafts in the ground, thought to date back round 4,500 years. Originally, they may have been used to guide people to sacred sites… or to warn them to stay away.

Using a combination of techniques, including ground-penetrating radar and analysis of samples taken from the sites themselves, researchers have managed to find 20 of these pits, forming points along a circle that's more than 2 kilometres (1.2 miles) in diameter. According to the team, these are traces of a monument unlike anything we've seen before.

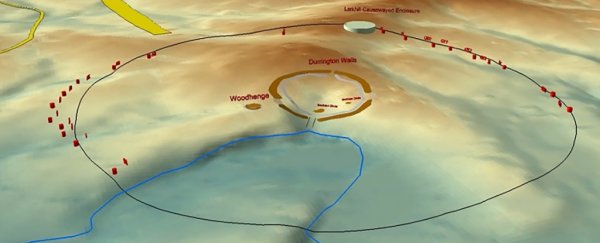

At the centre of this circle sit the famous prehistoric sites of Durrington Walls and Woodhenge. Another site, called the Larkhill causewayed enclosure, is just on the boundary, suggesting the shafts were deliberately and carefully positioned – in fact, the Larkhill site may have been their gateway.

"The sedimentary infills contain a rich and fascinating archive of previously unknown environmental information," says Earth scientist Tim Kinnaird, from the University of St Andrews in the UK.

"With optically stimulated luminescence profiling and dating, we can write detailed narratives of the Stonehenge landscape for the last 4,000 years."

Having been naturally filled in over the past few thousand years, the pits measure some 10 metres (nearly 33 feet) in diameter and over 5 metres (more than 16 feet) in depth. The discovery was made as part of the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project, led by the University of Bradford.

The shafts had previously been dismissed as sinkholes or dew ponds, but modern radar scanning techniques and magnetometry have shown how the original excavations went deep and straight into the ground.

The archaeologists think as many as 30 shafts might have been dug in total – only part of the circle has been discovered – but because of modern building development in the area, these 20 might be all that we're able to identify.

Bones and flint dug up from some of the shafts, as well as recovery of some of the sediment they've been filled in with, was used for radiocarbon dating. Less easy to establish is exactly how these pits were used, but there's plenty of scope for future research now that the shafts have been identified.

"As the place where the builders of Stonehenge lived and feasted, Durrington Walls is key to unlocking the story of the wider Stonehenge landscape, and this astonishing discovery offers us new insights into the lives and beliefs of our Neolithic ancestors," says archaeologist Nick Snashall, from the National Trust Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site, who wasn't directly involved in the research.

Those insights include a new perspective on just how good at engineering the Neolithic locals around Salisbury Plain actually were, several millennia ago. There's no way these pits could have been spaced and dug out without some clever maths and engineering nous being applied.

Just 3.2 kilometres (almost 2 miles) to the southwest of Durrington Walls is Stonehenge itself, another marvel of maths and engineering prowess, and constructed at around the same time - perhaps by the same people.

The iconic structure has long been a curious indicator of the way life was for the people who lived in the area in the Neolithic period, which in northern Europe came to an end around 1,700 BCE.

While there's a long tradition of pit digging for all kinds of uses stretching back thousands of years, the researchers say they've never seen anything like this. Further study may reveal more about these mysterious shafts, from a time that would have been very different to the one we're living in now.

"Seeing what is unseen! Yet again, the use of a multidisciplinary effort with remote sensing and careful sampling is giving us an insight to the past that shows an even more complex society than we could ever imagine," says Earth scientist Richard Bates, from the University of St Andrews.

"Clearly sophisticated practices demonstrate that the people were so in tune with natural events to an extent that we can barely conceive in the modern world we live in today."

The research has been published in Internet Archaeology.