We've known for a while now that type 1 diabetes is caused by the immune system turning against the body's insulin-producing cells. But exactly what causes this traitorous act has never been clear. A newly discovered 'hybrid' white cell could finally explain this, and possibly even help us understand the origins of a variety of other auto-immune disorders.

Research led by a team at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine has identified a unique variety of white blood cell displaying features of two of our immune system's most important cells.

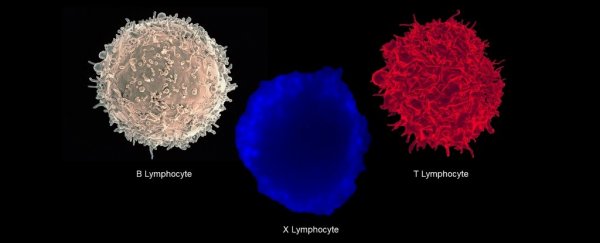

"The cell we have identified is a hybrid between the two primary workhorses of the adaptive immune system, B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes," says pathologist Abdel-Rahim A. Hamad from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Together, these two types of lymphocyte engage in a bounty hunt for invaders and rogue cells that put the body at risk.

B cells act as the dispatcher, providing important details that help identify the body's 'top most wanted' list.

After maturing in bone marrow, they head to places like the lymph nodes where they become familiar with chemical signatures called antigens – scraps of material left over from battles with past threats. Using these identifying features they produce antibodies that can alert the body to the same threat in the future.

T cells, on the other hand, can be thought of as the street-wise hunters out on the prowl for cells-gone-bad.

The variety known as cytotoxic or 'killer' T cell looks around the body for cells with antigens on their surface, and destroys them before they can do any harm.

Another type of T cell called a 'helper' tells immature B cells to prepare for war by dividing quickly and heading out into the field where they can distribute antibodies like wanted posters. After the dust settles, some of those B cells can stick around to serve as a reminder in case the threat returns.

Analogies aside, these actions depend on a complex array of hormones and interactions involving specific cell receptors - and they're bound to get it wrong sometimes.

One example is when T cells respond to insulin as if it's an antigen. Researchers have speculated this is the primary cause of type 1 diabetes, where insulin producing islet cells in the pancreas are ravaged early in life by an immune attack.

This involves a type of antigen-presenting cell, which include macrophages and B cells, with a variant surface marker commonly associated with autoimmune conditions like diabetes and coeliac disease called DQ8.

Insulin binds to DQ8, which would hypothetically cause T cells to run off half-cocked looking to kill anything that might resemble it.

"However, our experiments indicate that it is a weak binding and not likely to trigger the strong immune reaction that leads to type 1 diabetes," says Hamad.

There seems to be a missing piece to the story. So, the researchers went digging to find out what could turn a loose connection into a sure-fire hit, starting where they left off on earlier research on B cells.

Using blood samples taken from volunteers recruited via the Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Diabetes Center, they stumbled across a strange population of white cells displaying cell receptors for both T and B cells.

Further analysis revealed these cells had uniquely expressed genes, along with the activation of the kinds of genes associated with each individual cell line. It was a B cell, a T cell, and it's own special kind of cell.

"This probably accentuates the autoimmune response because one lymphocyte is simultaneously performing the functions that normally require the concerted actions of two," says Hamad.

The team discovered the B cell receptors on this strange dual expresser (DE) cell coded for a protein that could help explain the hyped-up insulin reaction.

Based on computer simulations, the protein – called x-Id – binds to DQ8 with a thousand times the strength of insulin. The result is a massive increase leap in the T cell response, which could potentially drive its war against the pancreatic cells.

"This finding, combined with our conclusion that the x-Id peptide primes T cells to direct the attack on insulin-producing cells, strongly supports a connection between DE cells and type 1 diabetes," says Hamad.

Both the peptide and hybrid white cells were more likely to be found in the blood of diabetic patients, adding to the likelihood that they could be responsible for the disease on some level.

It's not only type 1 diabetes that could at last have a detailed explanation. The researchers speculate these DE cells might play a role in other autoimmune disorders such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis.

Further research will help confirm the cell's actions and maybe even provide insight into potential early treatments for these debilitating immune conditions.

This research was published in Cell.