New research into the hormone somatostatin has the potential to change the general scientific consensus on how it influences Alzheimer's and how the disease begins to develop in the brain.

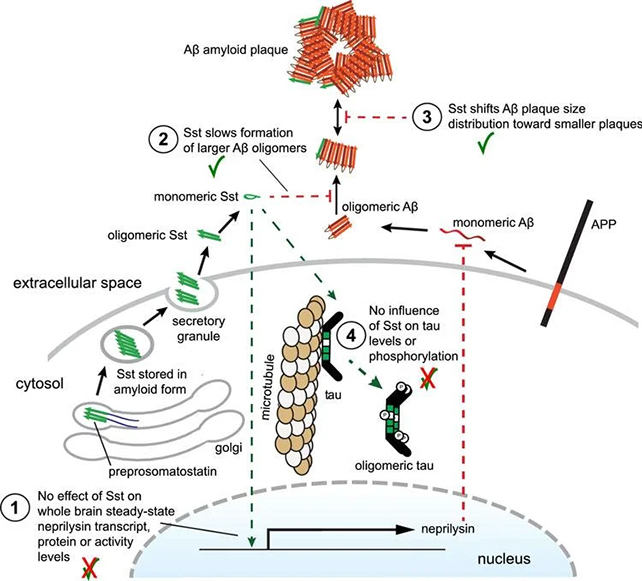

Somatostatin plays a role in many parts of our body. In previous studies, the hormone was also thought to drive the production of the enzyme neprilysin, which can degrade amyloid beta, the protein that clumps together and damages neurons in the brains of people with Alzheimer's.

The new study suggests that somatostatin actually influences amyloid-beta more directly, putting the brakes on the mechanisms by which the protein's monomer (single molecule) form combines into an oligomer (multi-molecule) form.

"The answer is that somatostatin has a significant effect, but it's not black or white," says Gerold Schmitt-Ulms, a neuroscientist at the University of Toronto in Canada. "It doesn't prevent clumping of the amyloid beta protein, but slows it down."

"This is important, but we don't know what this means for treatment yet."

Using a mouse model, Schmitt-Ulms and the team looked at the effects of somatostatin deficiency and amyloid-beta plaque aggregation and found that animals without the hormone tended to have more extensive, denser plaque buildup.

However, this didn't seem to be linked to the levels or activity of neprilysin, as was previously theorized; somatostatin is definitely playing some kind of role, but not the role that scientists thought.

The research follows an earlier study by some of the same researchers that showed how somatostatin binds to amyloid beta in the brain – and only in its oligomer form when links between molecules have started to be made.

"There isn't a lot of literature that explains how the environment in the brain can promote or inhibit amyloid beta forming into oligomers, so this is a nice vignette that shows that one molecule – somatostatin – seems to influence that first small oligomeric aggregation step," says Schmitt-Ulms.

Understanding how these chemical bonds happen at the smallest scales will be crucial in getting a better picture of how amyloid-beta plaques bunch together and how we might be able to stop them.

The balance of somatostatin is so important in the human body that selectively boosting it as a treatment wouldn't be easy, but it now gives researchers another avenue to explore in finding a cure for Alzheimer's.

"The evidence speaks for itself, and we stand by our conclusions, but the data can't answer what this means for therapeutics," says Schmitt-Ulms.

"They do, however, indicate that somatostatin – one of the first-ever molecules that were biochemically linked to Alzheimer's disease – may play a different role in the earliest stages of the disease than expected, and that in itself is important."

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.