The Antarctic research station that originally discovered the ozone hole in Earth's atmosphere during the 1980s is now facing a different kind of environmental crisis that's much closer to home.

A huge ice chasm nearby that was dormant for 35 years has started to split open again, and is encroaching toward the Halley VI Research Station, situated on the Brunt Ice Shelf in East Antarctica.

The chasm, which became active again in 2012, is moving northwards towards Halley VI at a rate of about 1.7 kilometres (1 mile) per year. While the crack is unlikely to open up underneath the station and swallow it whole, all indications are that if Halley VI doesn't relocate to safer ground, it will get cut off from the majority of the shelf and become adrift at sea.

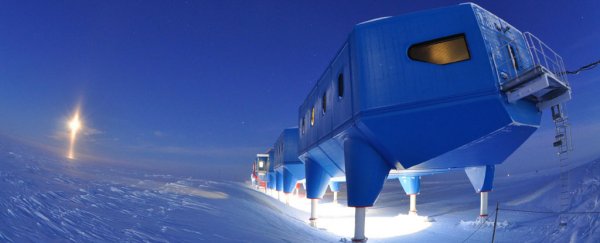

Fortunately, Halley VI, which is the sixth iteration of the Halley Research Station, was built with such extreme eventualities in mind.

The facility, which is operated by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), consists of eight connected station modules held up by ski-fitted hydraulic legs. Once these modules are uncoupled from one another, each can be towed by large tractors to new locations, which is what the plan is here.

"Halley was designed and engineered specifically to be re-located in response to changes in the ice," says BAS director of operations Tim Stockings.

"Over the last couple of years our operational teams have been meticulous in developing very detailed plans for the move and we are excited by the challenge."

Not that there isn't some drama to the mission, as the structure hasn't been moved since it was originally constructed in its present location in 2012.

But more pressing is that the Antarctic field season – which coincides with the start of summer in the Southern Hemisphere – only lasts nine weeks.

During this short window, the researchers will have to cart their entire research station piece by piece as far as they can towards its eventual destination – some 23 kilometres to the east (see the map below).

British Antarctic Survey

British Antarctic Survey

Their new home will see Halley VI situated on the eastern side of the chasm, before it cleaves the north-west tip from the remainder of the Brunt Ice Shelf.

The move will only be possible during the nine weeks of the field season, before harsh winter conditions descend upon the ice shelf again. The whole convoy is expected to take three years – i.e. three season windows – to complete its journey, and here's hoping that the chasm opening doesn't speed up in the meantime.

With the planet already losing enough ice to cover India this year, things aren't looking great.

"Antarctica can be a very hostile environment," says Stockings. "Each summer season is very short… And because the ice and the weather are unpredictable we have to be flexible in our approach."

What complicates the situation further is that another new crack was discovered in the ice shelf in October this year. This crevasse runs east to west along the ice shelf, northwards of where Halley VI is now.

It's significantly narrower and shallower than the chasm currently threatening the station, but it does cut off one of the routes used to resupply Halley VI with necessary provisions from time to time – and shows how constantly unforgiving this environment can be.

While the relocation effort is underway, the scientists stationed at Halley VI will continue their research as much as is possible, monitoring things like extreme space weather events, climate change, and other atmospheric phenomena.

"We are especially keen to minimise the disruption to the science programs," says Stockings.

"We have planned the move in stages – the science infrastructure that captures environmental data will remain in place while the stations modules move."

Life goes on it seems – even when you're racing to avoid being stranded on a drifting ice shelf in one of the most inhospitable places on Earth.