At the Davidson Seamount, off the coast of California, a world of wonder lurks on the seafloor.

There, in the shimmering warmth that seeps through from the volcano below, thousands of 'pearl' octopuses (Muusoctopus robustus) gather to mate, to nest, and to nurture their eggs to hatch.

Discovered in 2018, the nursery is the most spectacular octopus nesting site ever discovered.

Now, after multiple dives to monitor and observe the site, a team led by marine scientist James Barry of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) has figured out the allure of this special place: The warmth from the volcano accelerates the eggs' development, increasing the odds of survival.

"Thanks to MBARI's advanced marine technology and our partnership with other local researchers, we were able to observe the Octopus Garden in tremendous detail, which helped us discover why so many deep-sea octopus gather there," Barry says.

"These findings can help us understand and protect other unique deep-sea habitats from climate impacts and other threats."

The Octopus Garden, as it has come to be known, seems to be in a somewhat peculiar location, for octopus physiology.

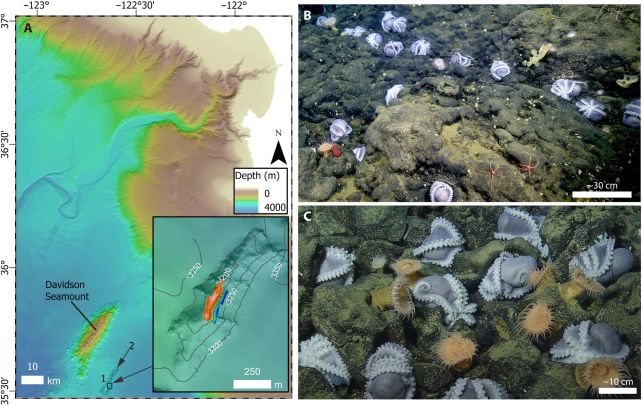

It's 3,200 meters (10,500 feet) below the surface of the ocean, in the permanent icy darkness of the bathypelagic. But the researchers counted 4,707 nesting females across a 2.5-hectare area at the center of the site; they estimated as many as 20,000 octopuses, male and female, across the entire nursery.

Octopuses, like many sea creatures, are cold-blooded; the average ambient temperature in the Davidson Seamount abyss, around 1.6 degrees Celsius (35 Fahrenheit), slows their metabolisms.

At that temperature, the eggs of the cephalopods – referred to as 'pearl octopuses' by the researchers thanks to their opalescent sheen – are expected to take five to eight years to hatch.

Over the course of three years, the researchers conducted 14 dives using a remotely-operated vehicle, extensively studying and documenting the octopuses. They carefully took note of distinguishing features, such as scars, as well as the locations mother octopuses chose to lay and huddle over their eggs.

The faint shimmering of water in the seamount was a clue about why the spot was chosen. It occurs when warmer water mixes with much colder water. This suggested a previously unknown hydrothermal system.

They found that the octopus nests tend to be clustered in crevices – and those crevices are places where warmth seeps from below the seafloor, heating the water to a relatively balmy 11 degrees Celsius (51 Fahrenheit) or so.

This temperature, the team found, is a lot more amenable to octopus metabolisms and egg incubation. By tracking individual octopuses, they found that the incubation period for the pearl octopuses had been shortened to around 21 months. The warmth had sped up the growth of the embryos, and the metabolisms of the mothers.

It's unclear whether the warmth is a requirement for the octopuses to nest, but it's clear that it is beneficial. The shorter incubation period dramatically reduces the chance of being eaten by a predator while the incubating octopuses are still vulnerable and unable to defend or flee, increasing their chances of survival in the long run, the researchers say.

"The deep sea is one of the most challenging environments on Earth, yet animals have evolved clever ways to cope with frigid temperatures, perpetual darkness, and extreme pressure. Very long brooding periods increase the likelihood that a mother's eggs won't survive," Barry says.

"By nesting at hydrothermal springs, octopus moms give their offspring a leg up."

The research has been published in Science Advances.