A new AIDS vaccine trial is about to begin in the US, and this one is a little different - the vaccine has been developed over the past 15 years by Robert Gallo, the scientist who first proved in 1984 that HIV triggered the disease.

The phase I trial will involve 60 volunteers and will simply test the safety and immune responses of the vaccine, so we won't know for a while whether it will be more effective than the other 100+ AIDS vaccines that have been trialled over the past 30 years. But extensive testing has been done in monkeys so far with positive results.

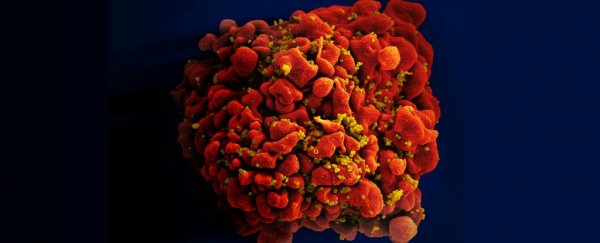

Although there have been some promising vaccine candidates in the past, the challenge with AIDS is that HIV directly infects white blood cells called T-cells, so it literally turns our immune system against us. That means that once the virus has entered a T-cell, it's invisible to the immune system.

The only chance we have to prevent infection is to trigger antibodies against the HIV surface proteins before that happens - something that's been equally difficult considering the fact that the retrovirus can regularly change its viral envelope to hide particular surface proteins.

But Gallo and his team at the Institute of Human Virology in the US think they may have now found a moment when the HIV surface protein, known as gp120, is vulnerable to detection - the moment the virus binds with our bodies' T-cells.

When HIV infects a patient, it first links to the CD4 receptor on the white blood cell. It then transitions, exposing hidden parts of its viral envelope, which allow it to bind to a second receptor called CCR5. Once HIV is attached to both these T-cell receptors, it can successfully infect the immune cell. And at that point, there's little we can do to stop it.

Known as the "full-length single chain" vaccine, Gallo's vaccine contains the HIV surface protein gp120, engineered to link to a few portions of the CD4 receptor. That goal is to trigger antibodies against gp120 when it's already attached to CD4 and is in its vulnerable transitional state, effectively stopping it from attaching to the second CCR5 attachment.

And before you say anything, Gallo himself admitted to Jon Cohen over at Science that full-length single chain vaccine is a "terrible name".

The trial is being run in collaboration with Profectus BioSciences, a biotech spin-off from the Institute of Human Virology, and Gallo explained that they've taken so long to get to this point because they've been extremely thorough in their testing on monkeys, and then had to scramble for funding to develop the drug into a human-grade vaccine.

"Was anything a lack of courage?" he asked Science. "Sure. We wanted more and more answers before going into people."

Let's hope that caution pays off, and we may finally have a viable contender for an AIDS vaccine on our hands. Watch this space.