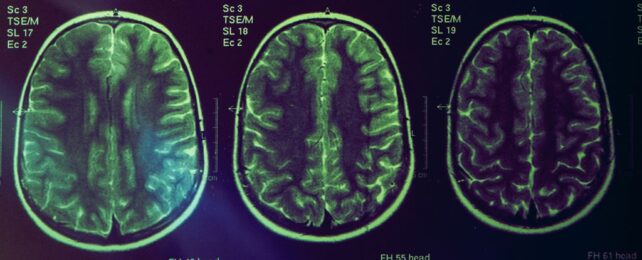

Decreases in brain volume are used as an indicator of Alzheimer's disease, yet the latest class of Alzheimer's treatments cause the brain to shrink even further.

A new study now suggests this might paradoxically be a good thing.

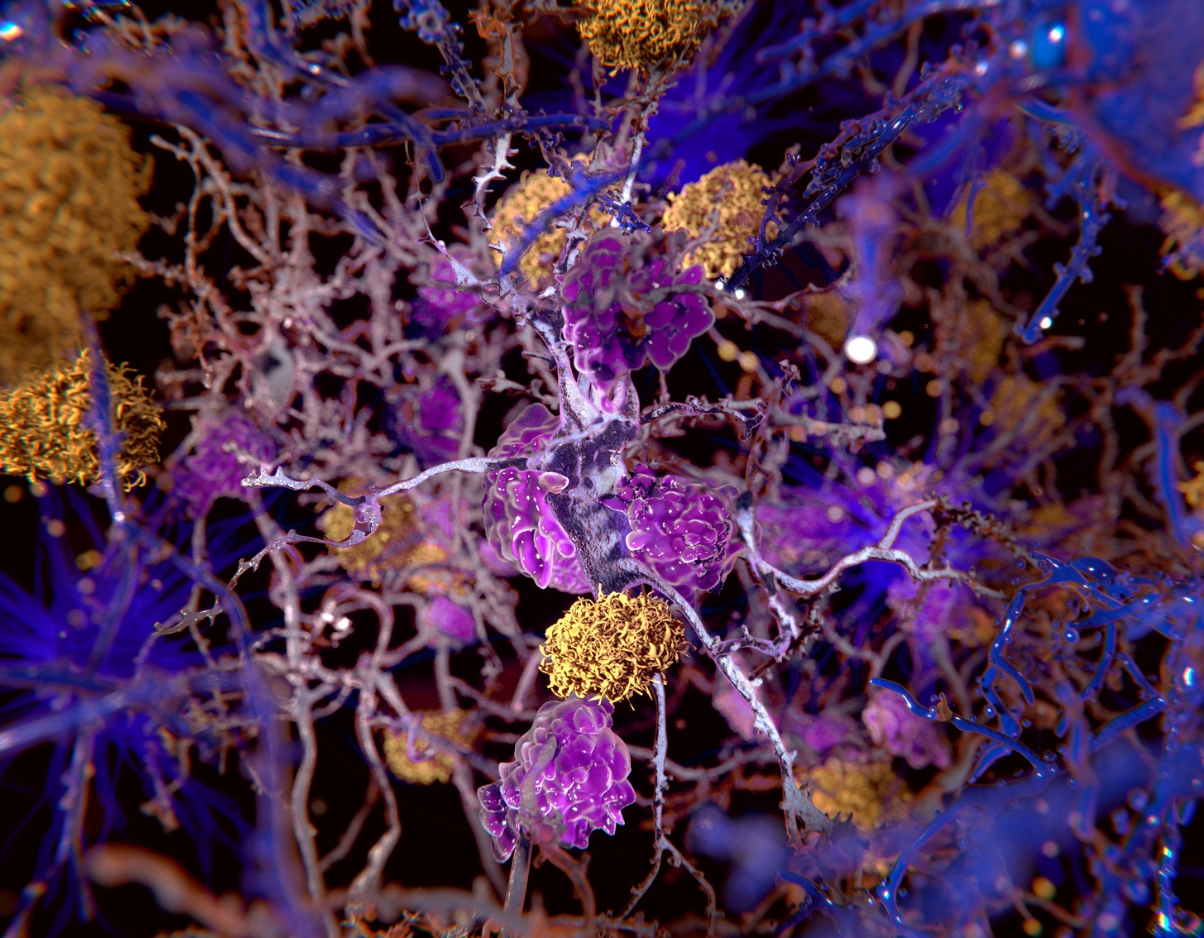

Neurosurgeon Christopher Belder from University College London (UCL) and colleagues found the loss of brain volume in patients undergoing new immunotherapy treatments is likely caused by a successful decrease of the suspicious protein clumps clogging Alzheimer's brains, rather than the drug destroying tissues.

"Amyloid immunotherapy has consistently shown an increase in brain volume loss – leading to concerns in the media and medical literature that these drugs could be causing unrecognized toxicity to the brains of treated patients," explains UCL neurologist Nick Fox.

"However, based on the available data, we believe that this excess volume change is an anticipated consequence of the removal of pathologic amyloid plaques from the brain of patients with Alzheimer's disease."

Belder, Fox, and colleagues analyzed data from twelve different Alzheimer's treatment trials targeting the naturally-occurring beta-amyloid proteins which clump excessively in patients with Alzheimer's.

While there is now some controversy around the protein clumps' role in Alzheimer's, several recent studies suggest any harm caused by the plaques may depend on surrounding molecules which share the protein's environment.

They found the extra brain volume loss was only present when treatments successfully reduced beta-amyloid proteins. What's more, the level of volume loss reflected changes in the levels of beta-amyloid.

"The volume occupied by beta-amyloid plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease is not trivial (around 6 percent of cortex according to post-mortem studies)," Belder and team explain.

"The extent of excess volume change seen in treated patients is considerably lower than this volume occupied by plaques."

Their proposed explanation is still incomplete, Belder and team caution, noting possible shifts in brain fluid makes multiple factors likely.

"Given that some of these anti-amyloid treatments are now in clinical use and others are in or entering clinical trials, it is vital to understand whether these volume changes are a signal of harm," the researchers warn.

"There are many unanswered questions, including the long term trajectory of volume changes. And, crucially, whether excess volume change after beta amyloid removal adversely influences long term outcomes."

The findings offer some reassurance against the risk of harmful side effects, but as data on long term use of these new medications is limited specialists are urged to proceed cautiously as the drugs become available.

"We are calling for better reporting of these changes in clinical trials, and for further evaluation to better understand these brain volume changes as these therapies enter more widespread use," says Belder.

This research was published in Lancet Neurology.