Neptune, it seems, has been keeping a few secrets. A teeny tiny moon has been found in orbit around the enigmatic outermost known planet - previously undetected, even though it's right here in our Solar System.

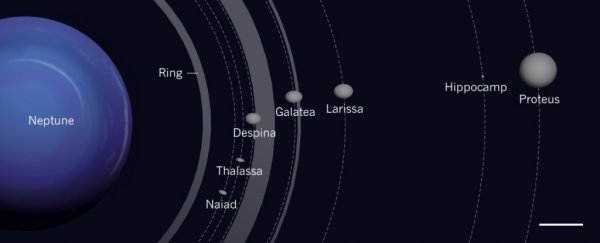

It's been named Hippocamp, after the half-fish, half-horse of Greek mythology (in keeping with Neptune's sea theme), and it's just 34 kilometres (21 miles) across. It brings Neptune's official moon count to 14.

Think about that for a second. Neptune is 4.5 billion kilometres (2.8 billion miles) from the Sun on average. That's over 30 times the distance between Earth and the Sun. And yet a team of astronomers has managed to spot a piece of rock just a little bigger than Olympus Mons.

It was a feat of both ingenuity and dogged persistence.

"The trouble with this moon is that it is too small to be seen in a single exposure of the telescope, even after 5 minutes," planetary astronomer Mark Showalter of the SETI Institute told ScienceAlert.

"However, it also moves fast enough that we could not combine multiple images, because the moon smears out."

He and a team of astronomers had not, initially, been looking for moons. Since 2004, they had been using the Hubble Space Telescope to study the evolution of Neptune's arcs - incomplete rings first imaged by the Voyager Mission in 1989. But the arcs were hard to see clearly, so the team needed to get creative.

"We came up with a technique to distort each image in a sequence based on our knowledge of orbital motion. It enabled us to 'stop' the Neptune system and allow us to combine eight five-minute exposures into one 40-minute exposure," Showalter said.

(Mark R. Showalter/SETI Institute)

(Mark R. Showalter/SETI Institute)

And there it was. Something strange, in Neptune's neighbourhood. "An extra 'dot' appeared in our images. That turned out to be Hippocamp … By finding the same dot in other images, and by showing that all the dots fit a single orbit, we confirmed the discovery."

Not even Voyager had seen this moon on its 1989 encounter with Neptune.

Previously known as Neptune XIV, the moon's discovery was actually first announced in 2013, but follow-up observations were required to fully understand its orbit. The full dataset covers the period between 2004 and 2016.

So what is Hippocamp? Where did it come from? Well, there's one clue: it orbits very closely to another of Neptune's small inner moons, the 420-kilometre (261-mile) diameter Proteus. And Proteus bears a scar - a giant impact crater called Pharos.

Neptune's inner moons, it's hypothesised, have had many encounters with comets. It's possible that an impact with a comet, sometime in Proteus's past, flung debris from the larger moon out into orbit around Neptune. Then, over time, some of it could have coalesced into Hippocamp, which is only two percent of the mass missing from the Pharos crater.

Where the rest went is unknown - but it's not impossible that it could have formed into one of the arcs or rings circling Neptune.

It's also not impossible that the moon formed another way. But Showalter told us he thinks the impact scenario is the most likely.

A size comparison of Neptune's inner 7 moons. (SETI Institute)

A size comparison of Neptune's inner 7 moons. (SETI Institute)

"For me, the most interesting thing about Hippocamp is that it shouldn't be there," he said.

"Based on what we knew beforehand about Proteus's orbital evolution, there was absolutely no reason for us to expect a moon at the location where Hippocamp turned up. That's one of the reasons why we think Hippocamp is a piece of Proteus that got left behind."

It's only a tiny moon, but Hippocamp has turned out to be pretty exciting. It could shed some light on how Neptune's rings, arcs and moons formed. And the technique reveals that there are still ways we can find to MacGuyver our technology to make new discoveries, even right on our own cosmic doorstep.

"The truth is that I very nearly missed this one. If I had not figured out a new way to process the data, we probably would not have seen Hippocamp," Showalter told ScienceAlert.

And he expects there are even more hidden surprises, out there in the far reaches of the Solar System.

"We know that Cassini found six moons of Saturn that were too small for Voyager to see. I am sure that there will be smaller moons of Uranus and Neptune, as well as a host of other surprises, that turn up when NASA and ESA finally send orbiters to Uranus and Neptune."

The team's paper has been published in the journal Nature.