Glioblastoma is one of the most common and aggressive forms of brain cancer, and it's one of the hardest to treat. There may be good news on the horizon, however.

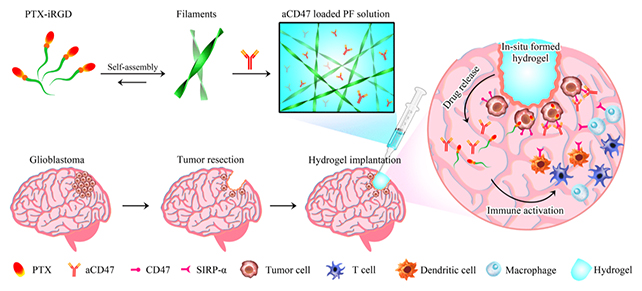

A newly developed hydrogel, tested on mice, cleaned up traces of glioblastoma tumors and stopped them from returning. The hydrogel was so effective that there was a "striking" 100 percent survival rate in the animals.

Although we can't be sure that the same treatments will achieve that level of success in humans, it's a hugely promising new approach.

Paclitaxel is the chemotherapy drug at the center of the gel, used to make nano-sized filaments for insertion into the brain. The drug is already approved for treating other cancers, including breast and lung cancer.

In the case of brain tumors, the delivery is key.

The hydrogel covers the cancer cavity and the thin grooves left by tumor removal evenly, releasing an antibody called aCD47 over several weeks. It seems the treatment reaches parts of the tumor site that other drugs can miss.

"We don't usually see 100 percent survival in mouse models of this disease," says Betty Tyler, a professor of neurosurgery from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

"Thinking that there is potential for this new hydrogel combination to change that survival curve for glioblastoma patients is very exciting."

That ability to deliver both drugs and antibodies together – offering both chemotherapy and immunotherapy simultaneously – is another part of what makes the hydrogel special. It's challenging to combine the two as they have different molecular structures.

Researchers describe the strategy as a "drug-delivered-by-drug", and in the tests, it seemed to boost the animals' immune systems. When glioblastoma tumors were reintroduced, the mice could fight them off on their own, without further treatment.

However, surgery was still required to remove the original tumor. When the gel was applied without first excising the tumor, the survival rate dropped to 50 percent.

"The surgery likely alleviates some of that pressure and allows more time for the gel to activate the immune system to fight the cancer cells," says chemical and biomolecular engineer Honggang Cui from John Hopkins University.

Glioblastoma remains incredibly tough to treat – partly due to a lack of protective T cells in the brain – but we're making progress. Small discs called Gliadel wafers, developed by the same research team behind this latest study, are currently used after tumor removal to stop the cancer from returning.

The researchers admit that it will be a "challenge" to convert their discoveries into practical treatments that work on the human brain.

"Despite recent technological advancements, there is a dire need for new treatment strategies," says Cui. "We think this hydrogel will be the future and will supplement current treatments for brain cancer."

The research has been published in PNAS.