After more than fifty years of trying, a potential new chlamydia vaccine has at last reached phase 1 clinical trials. Not only was the vaccine found to be safe and well-tolerated when administered to humans, it was also able to provoke a distinct immune response.

While this does not necessarily suggest full protection from chlamydia, researchers say these are promising early signs.

"Given the impact of the chlamydia epidemic on women's health, reproductive health, infant health through vertical transmission, and increased susceptibility to other sexually transmitted diseases, a global unmet medical need exists for a vaccine against genital chlamydia," says immunologist Peter Andersen from the Statens Serum Institut in Denmark.

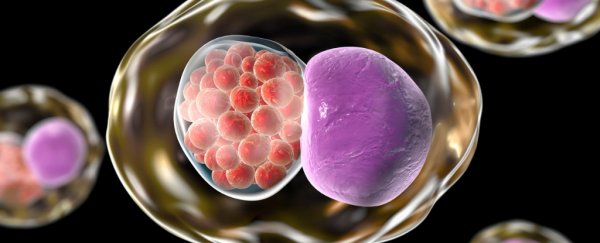

This is a hole that scientists have been trying to fill for decades with no success. The first attempts to create a chlamydia vaccine began way back in the 1960s, when researchers tried to produce a number of vaccines using the bacterium itself, Chlamydia trachomatis.

These studies unfortunately backfired, with some patients becoming more susceptible to the infection after vaccination. Without a clue as to what was going on, the idea was largely abandoned until recently.

Today, chlamydia is the most common sexually transmitted bacterial infection in the world and a growing threat to female fertility, despite antibiotic treatments and screening programs.

Over the past decade, as the number of infections continues to grow, chlamydia vaccine research has picked up steam, with a dozen studies published each year on average.

In all that time, only one of these vaccines has had enough potential to make it to human clinical trials. After conducting studies on animals, researchers from Imperial College London and Statens Serum Institut were at last given permission to conduct a randomised trial of 32 healthy women between the ages of 19 and 45.

These participants were split into three groups; the first of which was given a placebo vaccine three times at 0, 1 and 4 months apart. In the same way, the second and the third group were given a chlamydia vaccine that contained either added liposomes (CTH522:CAF01) or added aluminum hydroxide (CTH522:AH).

These two different combinations were selected in previous trials on mice and guinea pigs. At 4.5 and 5 months, participants were then given intranasal boosts of the vaccine, receiving five doses in total.

The sample size is admittedly small, as is typical at this stage of trials, but the results are cause for optimism. Phase I clinical trials are primarily designed to test for safety, and in the study no serious adverse events were reported, which means the research can continue on to larger trials (which may or may not reveal less common reactions). Any local reactions to the vaccine were mild and comparable to the hepatitis B vaccine.

Testing the immune response was only a secondary goal, but that's where this medicine really shines. While no participant in the placebo group received an immune response, every participant who received the vaccines showed a strong immune response, and this was boosted with every subsequent jab.

Interestingly, the vaccine with liposomes was consistently better at increasing serum antibodies, inducing a 5.6 higher response in immunoglobulins following intramuscular injection. What's more, these added liposomes also showed a stronger mucosal and cell-mediated immune response, both of which are important for an infection that lives within cells of the mucus.

In fact, the amount of immunoglobulins produced by this vaccine are similar to those induced by other licensed vaccines like the one for hepatitis B. In contrast, the intranasal doses didn't seem to add much at all.

As exciting as these long-awaited results are, they are only indicative of immune protection; they don't guarantee that this vaccine can stop a chlamydia infection. But even still, there's good reason to think that it might.

"Studies of antibodies in mice have found that antibodies in the vagina are the first line of defence against chlamydia infection, which suggests they are key to how effective the new vaccine may be," explains clinical development researcher Helene Juel from the Statens Serum Institut.

In other words, if these antibodies can target the bacteria before it enters the genital tract, it might be able to halt the progression of the infection, reducing future fertility issues.

More years of research will be needed before this vaccine is shown to be effective and marketable, but the work is already under way. The authors say they are planning phase II of their clinical trials, which is set to test the efficacy of the vaccine sometime this autumn.

"It's exciting for us just to be off the starting block with doing human clinical trials," Shattock told Time. "We need to encourage more trials to be done in this space, because it's such an important infection with such a big potential public-health gain."

For many, the dream is to one day combine the chlamydia vaccine with the HPV vaccine, so that we can protect young females from cancer and infertility at the same time.

The research has been published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.