The boat burial practices of the Viking people of Scandinavia from the 7th to 10th centuries are famous. But when a high-ranking Viking woman on a farm in Vinjeøra, central Norway, died in the latter half of the 9th century, something was different.

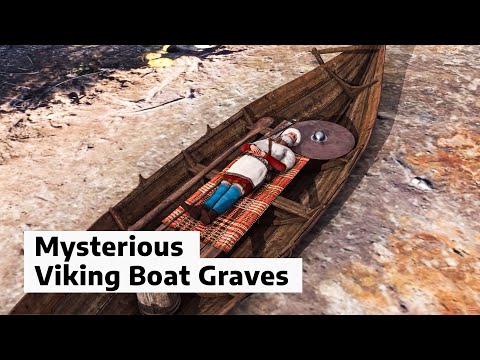

She was carefully dressed in fine clothes and arrayed with jewels and rich grave goods - gilded bronze brooches, a pearl necklace, textile craft implements, something that was perhaps food, and a cow's head. Then, she was laid in a newly constructed longboat.

But, rather than dig a new grave, the people of Vinjeøra dug up a larger longboat that had already been buried, corpse and all, 100 years prior.

The inhabitant of the larger longboat was an 8th century man. The woman's 7- to 8-metre (23- to 26-foot) longboat was carefully and neatly placed inside the larger 9- to 10-metre (30- to 33-foot) one, on top of the man's remains, and the whole assemblage re-buried.

It has archaeologists scratching their heads. Who was the man? Who was the woman? Were they connected in some way? Why bury them together?

"I had heard about several boat graves being buried in one burial mound, but never about a boat that had been buried in another boat," said archaeologist Raymond Sauvage of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) University Museum.

"I have since learned that a few double boat graves were found in the 1950s, at Tjølling, in the south of the Norwegian county of Vestfold. Still, this is essentially an unknown phenomenon."

The burial was found in connection to highway upgrades, and work was immediately undertaken to excavate the site. It was in extremely poor condition, with the wood of both boats almost entirely rotted away. It was poor soil for bone preservation, too - not much was left of the dead, either.

However, a few key elements were left behind. The keel of the smaller boat remained intact and in place, as did the metal studs used to construct the boats. That's how the archaeologists were able to reconstruct where the vessels had lain.

The metal grave goods were also intact, and, wonderfully, skull fragments belonging to the woman. Scientists may be able to conduct analyses on the bone, such as isotope analysis that can reveal where the woman lived and how she ate.

DNA analysis could reveal more information too - such as what she looked like, who she was descended from, how old she was when she died, and how healthy she was.

(Raymond Sauvage/NTNU University Museum)

(Raymond Sauvage/NTNU University Museum)

Of particular interest among the grave goods, the archaeologists said, was a cross-shaped brooch. Its shape and the pattern on its face suggest that it was once part of a horse harness made in Ireland.

This tells us that the woman probably belonged to a family that participated in raids across the ocean - an important facet of the Viking culture at this time.

"It was common among the Vikings to split up decorative harness fittings and reuse them as jewellery. Several fastenings on the back of this brooch were preserved, and were used to attach leather straps to the harness. The new Norse owners attached a pin to one of the fastenings so it could be used as a brooch," explained historian Aina Heen Pettersen of NTNU.

"Using artefacts from Viking raids as jewellery signalled a clear difference between you and the rest of the community, because you were part of the group that took part in the voyages."

As for the man, not a trace of him remained but his grave goods - a sword, shield and spear. They probably didn't belong to the woman, because there were two boats, and the sword was in an 8th century style.

Who he was and why the woman was buried with him is unclear, but it's likely that the two were related. Family was deeply important to the Vikings, not just for status reasons, but for legal reasons, too.

"The first legislation on allodial rights in the Middle Ages said you had to prove that your family had owned the land for five generations. If there was any doubt about the property right, you had to be able to trace your genus to haug og hedni - i.e. to burial mounds and paganism," Sauvage said.

"Against this backdrop, it's reasonable to think that the two were buried together to mark the family's ownership to the farm, in a society that for the most part didn't write things down."

For now, precious little is known about this possible family relation, but analysis on the remains is ongoing - so we might learn more about this strange burial eventually.