A Miocene-era shift from dense forests to open plains may have caused ancient hominids to move from vowel-based to consonant-based calls, a new study says.

The UK researchers monitored acoustic properties of recorded orangutan calls, believed to resemble early human sounds, projected across an African savannah to study how the environment shaped our ancestors' ability to speak.

University of Warwick language psychologist Charlotte Gannon and colleagues describe Africa's changing paleo-climate as an "ecological black-box" of spoken language evolution that vocal hominids entered, from which verbal humans came out of millions of years later.

Their research suggests our hominid ancestors may have made use of proto-consonants to communicate effectively in a transforming environment.

"The ecological settings and soundscapes experienced by human ancestors may have had a more profound impact on the emergence and shape of spoken language than previously recognized," writes the team in their published paper.

Over the past 17 million years, grasslands have expanded across Eurasia and Africa due to continental tectonic movement, global cooling, and aridification.

Archaeological finds and paleoecological inferences allow us to piece together how these changes impacted hominid anatomy and behavior, but the lack of soft tissues in the fossil record prevents reconstruction of the evolution of vocal signals and spoken language.

"By taking advantage of orangutans' arboreal consonant-like and vowel-like calls and moving them to an open landscape setting," Gannon and colleagues explain, "we can recreate, as close and realistically as it is possible today, the scenario in the Middle and Late Miocene (16–5.3 mya) when hominids transitioned down from trees to an open landscape."

The researchers used archive recordings of 20 wild orangutans' calls in syllable-like combinations and replayed them across a South African savannah habitat.

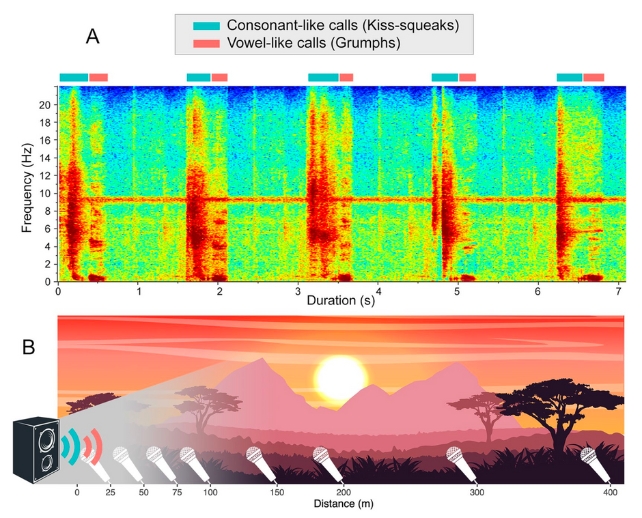

The 487 calls from Sumatran (Pongo abelii) and Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) included consonant-like kiss-squeaks and 'grumphs' that sound like vowels. You can listen to the two sounds here.

In order to determine the calls' audibility at various distances, they were re-recorded 25 meters (82 feet) apart over a distance of 400 meters. The researchers found vowel-like calls, like the a's and e's in our words, didn't carry as effectively as the consonant-like calls, like the b's and d's.

Vowel-based calls were much less audible than consonant-based calls after 125 meters, while consonant-based calls showed a slight decline in audibility after 250 meters.

At 400 meters, about 80 percent of consonant-based calls could be heard, compared to less than 20 percent of vowel-based calls. This indicates that calls based on consonants work considerably better when broadcast over open land.

"Where dense forests had offered equivalent performance for both call categories," the authors write, "the newly emerging dry and open landscapes offered superior transmission efficiency to consonant-like calls over mid and long distances."

An explanation for some characteristics of modern spoken languages may lie in the fact that early stages of speech evolution were more adept at perceiving consonants than vowels.

The team says moving to the open plains may have been crucial in hominid vocal communication, as consonants are predominant in modern human languages.

One example is the role of consonants as natural speech cues. People learning a language often use these to visually divide sentences and create processing pauses when none exist.

"In the new ecological settings, hominids now had an element available –consonant-like calls – in their vocal repertoire with enhanced perceptibility, if and when required," the authors conclude.

"The ecology of ancient hominids may have molded human modern verbal behavior to a larger extent than hitherto appreciated."

The study has been published in Scientific Reports.