A single injection of an experimental gene therapy treatment may be all that is required to permanently stop a female cat from reproducing, according to a small, proof-of-concept study.

Of the more than 600 million-some domestic felines that wander our planet, an astounding 80 percent are believed to be strays, void of owners or homes.

This potential new sterilization method could help control stray cat populations more safely and efficiently than surgically removing a cat's ovaries or uterus, which requires trapping, neutering, and releasing females.

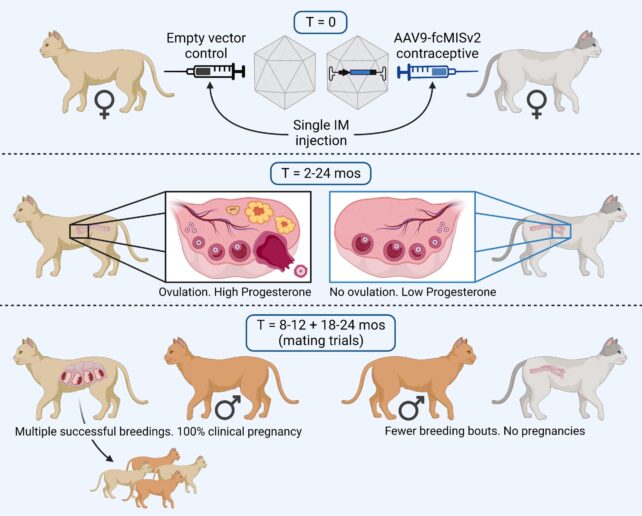

In this case, the treatment involves the Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), which connects to receptors in the ovary and helps regulate ovulation.

Delivered by intramuscular injection, it causes the cells to produce extreme levels of AMH, a technique previously shown to suppress the development of follicles in the ovary in mice and induce permanent contraception.

This new study used nine female felines, six of whom (Betty, Dolly, Jacque, Abigail, Barbara, and Mary) received the gene therapy treatment. For comparison's sake, three (Michelle, Nancy, and Rosalyn) were not.

All nine cats were involved in two 4-month-long mating trials, housed with a male cat on weekdays for eight hours at a time, and monitored for breeding interactions, along with weekly ultrasounds to assess whether they were pregnant.

All three control kitties conceived after their first breeding interaction, giving birth to litters of between two and four kittens. However, none of the six treated cats became pregnant.

The researchers conclude the sterilizing injections were safe and effective at permanently suppressing ovulation in all six cats.

Even better, two years after the cats received their injections, none showed any adverse reactions.

AMH levels in their blood serum were somewhat reduced after the first year, but they remained above a target threshold two years on. Further studies are needed to see how long these effects might last.

"We show that this vectored contraceptive prevents breeding-induced ovulation, results in complete infertility, and may constitute a safe and durable strategy to control reproduction in the domestic cat," researchers write.

As well as acting on the ovaries, the surge of AMH might also impact parts of the cat's brain, possibly inhibiting sexual or reproductive behavior via hormones, too.

"All three control females mated repeatedly with both males, whereas four of the six treated females rebuffed every mating attempt by the breeder males during both mating trials," researchers write.

Further studies are needed to see how gene therapy treatment changes neural activity in parts of the brain involved with reproductive behavior.

But initial results suggest that gene therapy can suppress ovulation without compromising the other roles that the ovary and uterus play in animal health.

For decades, officials have been surgically sterilizing stray cats so as not to euthanize them, but it's unclear if the policy actually works in reducing stray cat numbers or saving their lives on the streets.

Many of these neglected, free-roaming cats are responsible for killing native wildlife or spreading disease, and as they reproduce, their numbers continue to swell.

For each litter of kittens a stray cat has, approximately 75 percent of the offspring die before they reach their sixth month. But there isn't enough hard data to say whether sterilization programs help that death toll.

In remote areas, the practice is made even more difficult. In Australia, millions of cats out in the bush have been culled with poisonous food as opposed to sterilization for this very reason, and yet the public backlash has been extreme.

Over the years, scientists have been exploring more ethical methods of cat control, including contraceptive pills or implants.

Gene therapy injections are another option to explore.

The study was published in Nature Communications.