The human brain is a pretty damn amazing organ. Get rid of one bit, and sometimes the brain will just say "I've got this" and figure out how to repurpose something else.

Take the man with damage to 90 percent of his brain who is out there living his best life. Or the woman who lived for 24 years without ever knowing she was missing her entire cerebellum.

But an incredible new case report shows just how well the human brain is able to recover after losing a large part of its visual system.

When he was nearly seven years old, a boy – referred to in the paper as 'U.D.' – underwent a surgery called a lobectomy, having a third of the right hemisphere of his brain removed in an attempt to control seizures.

Doctors removed the right occipital and posterior temporal lobes, which are incredibly important for vision and word processing.

Although the removal sounds terrifying, the surgery actually has a high success rate for stopping seizures, despite being a very rare procedure, which is only considered for less than 10 percent of patients who have medically intractable epilepsy.

What the researchers found after the operation was that although U.D. could no longer see on his left side, his brain's left hemisphere compensated for visual tasks the missing parts of the right hemisphere would usually have done, such as recognising faces and objects.

"The only deficit is that he cannot see the entire visual field. When he is looking forward, visual information falling on the left side of the input is not processed, [but] he could still compensate for this by turning his head or moving his eyes," said Marlene Behrmann, a neuroscientist from Carnegie Mellon University.

"Moreover, by tracking the changes in the brain as U.D. developed, we were able to show which parts of the brain remained stable and which were reorganised over time. This offers insight into how the brain can remap visual function in the cortex."

Besides the vision loss, the researchers say the missing part of the brain doesn't really seem to affect U.D. in everyday life. Both before and after his surgery, he had an above-average IQ, and his language and visual perception skills are age-appropriate.

"I suspect that he doesn't have obvious awareness that he is missing that information," Behrmann explained to LiveScience.

"It's a little bit like, everybody's got a blind spot," but you aren't aware of it, she added.

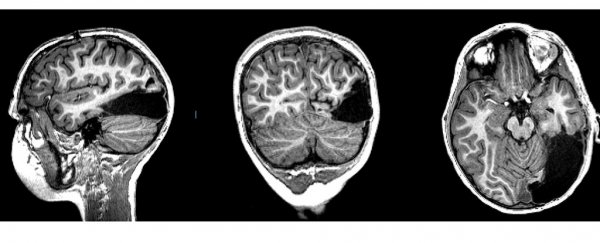

To make their findings, the researchers monitored U.D.'s brain using an fMRI machine for three years, and tested him on certain visual and behavioural tasks, comparing him against 11 age-matched boys who hadn't had the procedure.

In tests, U.D. could easily recognise objects and scenes – as well as he could before the lobectomy – and his reading proficiency remained above average.

"These findings provide a detailed characterisation of the visual system's plasticity during children's brain development," said Behrmann.

"They also shed light on the visual system of the cortex and can potentially help neurologists and neurosurgeons understand the kind of changes that are possible in the brain."

At this point, the researchers don't fully understand how U.D.'s remaining brain is able to take on these new tasks without compromising other aspects of his cognitive processing, but the flexibility he's shown may be something to do with his age.

Back in late 2017, a different seven-year-old stunned researchers because he was missing the entire visual section of his brain, and was still able to see.

Basically, we're still scratching the surface when it comes to what our brains can do, but their ability to compensate is truly astounding.

The research has been published in Cell Reports.