Damage to the skin isn't always just surface-level. New research has found flesh wounds can set off health issues that go beyond skin deep, with impacts reaching as far as the gut.

We've known for a while that there's a link between gut and dermal health, but most scientists had commonly assumed the microbes in our digestive system affected the skin, rather than the other way around.

Now, a team led by dermatologists from the University of California San Diego has found direct evidence for a skin-gut axis in mice, showing that damage to the skin throws the intestines' defenses off balance and changes the composition of the gut microbiome.

There are several organs that come into contact with the 'outside' world, skin being the most obvious. Other organs, like the gut and lungs, also have barriers that define and defend the body's borders.

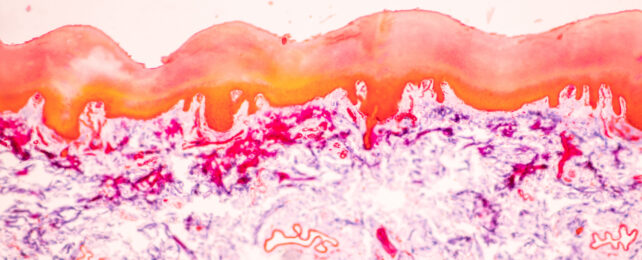

These barriers consist of epithelial tissues that act as armed guards, limiting limit the overgrowth of otherwise welcome microbes (think the 'good' gut bacteria happily feasting on your breakfast, or the mostly-harmless mites currently vacuum cleaning your face), and prevent invasion by unwelcome intruders like Escherichia coli, blood flukes, and Candida fungus.

Curiously, injury to one epithelial surface can occasionally mean changes to other distant organs at the same time. Inflammation in the bowel has been linked with damage to the lungs, for example.

To test their theory of a skin-gut axis, the team cut 1.5 centimeter (about half an inch) incisions in the skin of one group of mice. Then, they compared their feces to those of a control group of mice to see if there were any differences in the groups' gut microbiomes.

The mice that had been wounded had more disease-causing bacteria and fewer beneficial bacteria in their feces, indicating a significant alteration in microflora.

Similar results emerged from a subsequent experiment in which mice were genetically altered to produce more of an enzyme that breaks down the molecule hyaluronan (aka hyaluronic acid, or HA).

This increase in enzyme mimicked an aspect of skin injury without actually wounding the mice, to pinpoint the mechanism behind this skin-gut link. HA plays a crucial role in tissue injury and repair, and is released locally from the inner layer of the skin if it is wounded, or inflamed as a result of conditions like psoriasis.

The researchers also treated mice to induce digestive disorder colitis in order to investigate any relationship between dermal damage and the severity of the gut condition.

Both the mice with skin wounds and those with HA damage experienced much worse cases of colitis than the control groups. Separate mice received fecal transplants from those in the initial experiments, revealing that colitis susceptibility was transferred along with the transplanted gut microbiome.

"Prior studies have observed dysbiosis in the gut microbiome of individuals with inflammatory skin disease, it had been assumed that microbes in the gut were influencing the skin," the authors write.

And although studies in humans will be needed to confirm this, the authors think "these findings provide an unexpected explanation for the association between skin and intestinal diseases in humans."

This research is published in Nature Communications.