Distances in space are hard to measure. Unless you know how intrinsically bright something is, working out how far away it is becomes a little complicated.

Yet knowing a distance can make a huge difference to how we interpret data. It's not unheard of for astronomers to have to revise their findings based on a new distance measurement of an object.

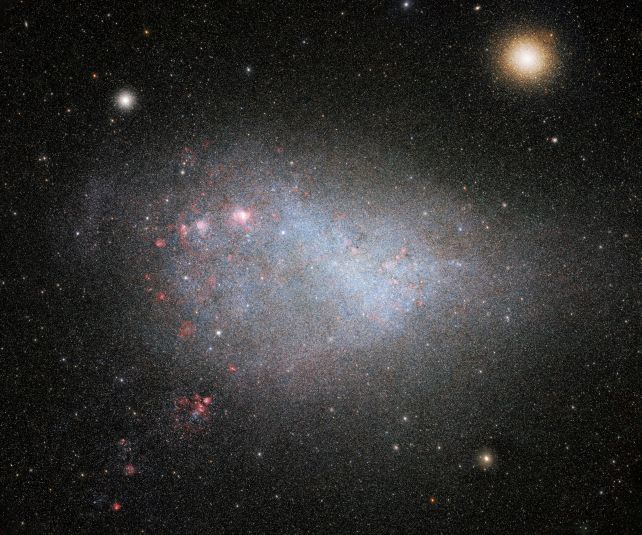

What is unusual is when that happens with something humanity has been staring at for millennia. Astronomers have just now discovered something shocking about one of the most well-known objects in Earth's sky. The Small Magellanic Cloud, new analysis suggests, is not one tiny galaxy orbiting the Milky Way, but two.

How could we make this mistake? The two discrete stellar populations, argues a team led by astronomer Claire Murray of the Space Telescope Science Institute, are superimposed along our line of sight. Their data suggest that the rearmost blob of stars hangs out some 16,000 light-years behind the other.

The findings, accepted into The Astrophysical Journal and uploaded to preprint resource arXiv, make a compelling case for the double nature of what we had previously interpreted as a single object.

The Small Magellanic Cloud is one of several dwarf galaxies orbiting (and slowly being subsumed into) the Milky Way. It's about 200,000 light-years away, around 7,000 light-years across, and has a mass of about 3 billion Suns. It's also paired with another galaxy that appears nearby in the sky, the Large Magellanic Cloud, about twice the size of the Small Magellanic Cloud. The two orbit each other as they orbit the Milky Way.

Actually, the hints that the Small Magellanic Cloud might not be what it seems have been coming in since the 1980s. The way the fog of stars moves seems strange – the interstellar gas environment doesn't seem to match up with other properties of the dwarf galaxy, and there seem to be at least two distinct populations of stars within it.

Previous research thought that the Small Magellanic Cloud might be odd because it has been gravitationally disrupted by interactions with the Large Magellanic Cloud, but the shape and dynamics of the dwarf galaxy remained inconclusive.

Murray and her colleagues conducted a thorough investigation of the space cloud to try and find out once and for all. They studied data from the Gaia survey, a project to map the three-dimensional positions and velocities of stars in the Milky Way with the highest precision yet. And they used data from a galactic survey conducted using the Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder radio telescope to study in detail the makeup of the gas that fills the Small Magellanic Cloud in the space between the stars.

Their study found that the Small Magellanic Cloud consists of two distinct populations of stars of similar gas mass, separated by a significant distance. Each population has its own interstellar gas signature, and the way the stars move in each is also distinct.

The team's measurements suggest that the closer of the two populations is around 199,000 light-years away; the more distant one is 215,000 light-years away – a difference roughly equivalent to half the distance between the Sun and the centre of the Milky Way. This is, the researchers say, broadly consistent with previous estimates of the line-of-sight structure of the Small Magellanic Cloud – but it's also the most compelling evidence yet.

The reason we have been unable to discern between them with certainty previously is because one sits directly behind the other along our line of sight, close enough together to almost – but not quite – look like one population of stars in our night sky.

The Small Magellanic cloud is a well-known and beloved feature of the southern sky. It has been observed for at least thousands of years by Indigenous astronomers in Australia, South America, and Africa.

And, with its larger sibling, it will continue to gleam in the sky for eons to come; but its demise is imminent. It's gradually falling into the Milky Way, as many other galaxies before it have done. This is an important part of how galaxies slowly grow, over billions of years.

Thanks to the Magellanic Clouds, we have a front row seat to this process in action.

The research has been accepted into The Astrophysical Journal, and is available on arXiv.