Back in May 1967, at the height of the cold war, all three of the United State's early warning system radars - designed to let them know if the Soviet Union had launched a ballistic missile - were disrupted at exactly the same time.

Assuming they'd been jammed, the US Air Force took it as an act of war, and authorised the mobilisation of aircraft and troops to retaliate against the Soviet Union.

They had their finger on the button of all-out nuclear war, but at the last minute, a group of pioneering scientists were able to show that the radars were actually disrupted by an incredibly powerful solar flare - not an attack - defusing the situation and kick-starting the US's current research into solar activity.

Almost 50 years later, we're only just hearing about the full extraordinary series of events, thanks to a new report in the journal Space Weather.

"Had it not been for the fact that we had invested very early on in solar and geomagnetic storm observations and forecasting, the impact [of the storm] likely would have been much greater," said lead researcher Delores Knipp from the University of Colorado in Bolder.

"This was a lesson learned in how important it is to be prepared."

Despite the fact that the May 1967 solar flare is listed as one of the most significant solar storms of the past century, Knipp explains that it's been of "mostly fading academic interest".

She decided to revisit the event to get an idea of what kind of impact a similar solar storm would have today - not just on our atmosphere, but on society. After all, we're much more reliant on our telecommunication systems now than we were 50 years ago.

Knipp and her team waded through all the reports on the 1967 solar storm, and for the first time, spoke to retired US Air Force officers involved in the event on the record. That's how she discovered just how close the US came to launching a 'retaliatory' attack.

She says the events - which sound like something out of a spy novel - are a reminder of just how important geoscience and space research is to national security.

So what actually happened to almost start World War III? The US military began monitoring solar activity and space weather - disturbances in Earth's magnetic field and upper atmosphere - in the late 1950s.

By the '60s, a whole new branch of the Air Force - the Air Weather Service (AWS) - was established to routinely monitor solar flares, and see how they could affect Earth.

Solar flares are brief blasts of high-energy radiation from the Sun's surface, often forewarned by sunspots, and when they're aimed at Earth, they can cause geomagnetic storms that can disrupt radio communications and power line transmissions.

By 23 May 1967, researchers were watching the Sun's activity daily, and saw a flare big enough to be visible to the naked eye. From this, they detected unprecedented levels of radio waves being blasted our way.

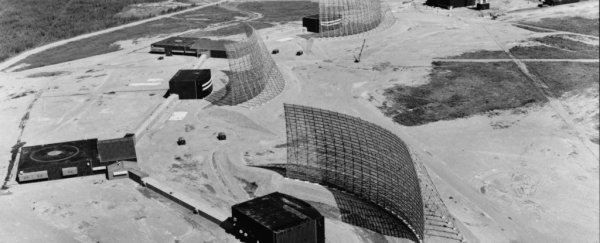

They forecast that a significant worldwide geomagnetic storm would occur within 36 to 48 hours - but even though we now know that this type of activity can hit us with radio waves earlier than that, no one at the time considered that the flare might affect the Air Force's Ballistic Missile Early Warning System, located in Alaska, Greenland, and the UK.

Retired Colonel Arnold L. Snyder, a solar forecaster at the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), was on duty on May 23 when the three radar sites stopped working, and remembers that the command post asked about any solar activity that might be occurring that day.

"I specifically recall responding with excitement, 'Yes, half the Sun has blown away,' and then related the event details in a calmer, more quantitative way," said Snyder.

Looking at the solar forecast, Snyder realised that the three early warning sites were all in sunlight and could therefore have been 'jammed' by radio emissions coming from the Sun - not the Soviet Union.

As the solar radio emissions died down, so did the interference, which provided further evidence that the radars hadn't gone down as part of an attack.

Thankfully, that information made its way up the chain of command - possibly all the way up to President Lyndon Johnson, Knipp suggests - in time for the Air Force to avoid military action.

The geomagnetic storm that followed around 40 hours after the initial radio burst went on to disrupt US radio communications in "almost every conceivable way" for almost a week, and was so strong that the Northern Lights were visible as far south as New Mexico.

That event led the military to realise how important accurate space weather forecasting was, and they built a stronger research team - we now have the Solar Dynamics Observatory in space monitoring the Sun constantly.

But it still acts as a reminder today of just how much these powerful flares from the Sun can influence our little planet.

"I thought it was fascinating from a historical perspective," said Morris Cohen, an electrical engineer from Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, who wasn't involved in the study.

"Oftentimes, the way things work is something catastrophic happens and then we say, 'We should do something so it doesn't happen again,'" he said. "But in this case there was just enough preparation done just in time to avert a disastrous result."

Thank you, science.