The long-standing mystery about the origin of the Martian moons could be a step closer to being solved.

A space probe has come within dozens of kilometers of the larger of the two satellite siblings to capture data about what lies beneath its scored and cratered surface.

"Whether Mars's two small moons are captured asteroids or made of material ripped from Mars during a collision is an open question," says astronomer Colin Wilson of the European Space Agency (ESA). "Their appearance suggests they were asteroids, but the way they orbit Mars arguably suggests otherwise."

Phobos, named for the ancient Greek deity of fear and panic, is the larger of the two moons at 22.2 kilometers (13.8 miles) across, and orbits Mars at an average distance from the surface of around 6,000 kilometers.

Deimos, after the Greek god of dread and terror, is just 12.6 kilometers (7.8 miles) across, and has a much greater average orbital distance of around 20,000 kilometers from Mars.

They're both rather peculiar objects, rather unlike our own companion in many ways. There are also some interesting differences between the two.

While Deimos is moving away and may one day escape Mars entirely, Phobos is moving towards Mars on a decaying orbit that shrinks by 1.8 centimeters (0.7 inches) each year, a journey that could see it tear apart to form a ring within the next 100 million years or so.

It's also unclear where they came from. Multiple compelling lines of evidence suggest that our Moon broke off from Earth in a giant collision, but Mars and its moons, millions of kilometers away, aren't as easy to study.

Compositionally, Phobos and Deimos seem quite similar, suggesting that they might have come from the same source; and that composition is also similar to a group of asteroids. But they also have similar tidy orbits that are nearly circular and stick pretty closely to the Mars equator, a characteristic that isn't typical of captured asteroids.

One way to look for answers is to peer under the hood, so to speak – to find out what's lurking under the surface of the moons. So ESA sent their Mars Express orbiter for a Phobos flyby, skimming within 83 kilometers (about 51 miles) of the potato-like satellite. For context, the Karman line that separates Earth atmosphere from interplanetary space lies at about 100 kilometers altitude. A flyby at just 83 kilometers is close.

"We didn't know if this was possible," says Mars Express flight controller Simon Wood of ESA. "The team tested a few different variations of the software, with the final, successful tweaks uploaded to the spacecraft just hours before the flyby."

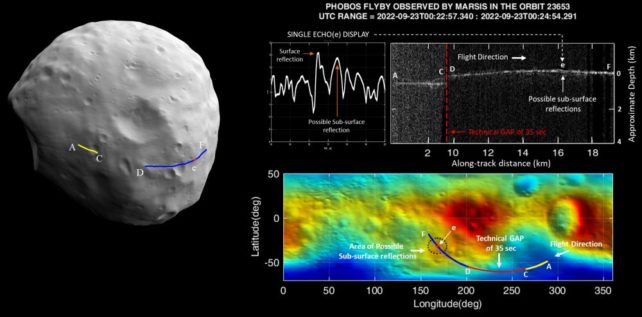

The flyby itself took place towards the end of September. The aim: to use an instrument called the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS) to probe below the surface of Phobos.

This is a radar instrument that sends low frequency radio waves at Mars; the way these waves bounce back from different materials below the surface allows scientists to figure out what might be there.

This is how scientists got an inkling there might be liquid water lakes (or clay deposits, or volcanic rock deposits, or layers of rock and ice) buried beneath the Martian southern polar ice cap. Now, the instrument is getting set to demystify the internal structure of Phobos.

"We are still at an early stage in our analysis," says astronomer Andrea Cicchetti of the National Institute for Astrophysics in Italy, which operates MARSIS. "But we have already seen possible signs of previously unknown features below the moon's surface. We are excited to see the role that MARSIS might play in finally solving the mystery surrounding Phobos's origin."

Over the next few years, Mars Express will be making even closer flybys of the lumpy little moon. From 2023 to 2025, the probe will swoop in, the team hopes, as close as 40 kilometers to Phobos's surface. This will provide opportunities to collect even more data on its interior structure.

In addition, space agencies around the world are collaborating on the Martian Moons eXploration mission. This ambitious project aims to send a probe to both Phobos and Deimos and study them in detail – and collect a sample from Phobos and bring it back to Earth for detailed analysis.

Perhaps then we'll finally have an answer on the birthplace of the two tiny Martian oddballs.