The biggest known canyon in the Solar System is getting the star treatment in new images from the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter.

As it whooshed by in Martian orbit, the spacecraft captured a pair of gouges in the planet's surface that make up part of the Valles Marineris, a system of canyons known as the Grand Canyon of Mars.

The Martian Grand Canyon, however, makes the Earth version seem like a canyon for ants.

At 4,000 kilometers (2,485 miles) long and 200 miles wide, Valles Marineris is almost 10 times longer and 20 times wider than the vast canyon system found in North America. Earth has nothing that comes even close to comparing to Valles Marineris, which makes the feature intensely interesting to planetary scientists.

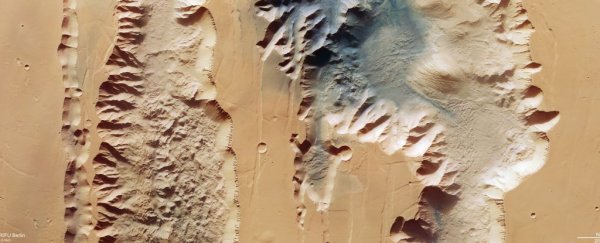

The segment images by Mars Express include sections of two chasmata, Ius on the left and Tithonium on the right. Close study of the details of these incredible natural structures can help scientists understand Mars' geology and geological history.

The location of the two chasmata. (NASA/MGS/MOLA Science Team)

The location of the two chasmata. (NASA/MGS/MOLA Science Team)

For example, Mars seems to be tectonically extinct now, with its crust fused into one discrete layer that encases the planetary interior. This is in contrast to Earth, the crust of which is divided into plates that can shift around, with a whole range of consequences.

Valles Marineris, scientists think, formed back when Mars did have tectonic plates. Recent research has proposed that the canyon system formed as the result of a widening crack between plates, a long time ago. This makes Valles Marineris very interesting indeed.

The images from Mars Express make the canyon look relatively shallow, but the two chasmata are incredibly large; the full resolution version is approximately 25 kilometers per pixel. Ius Chasma extends 840 kilometers in length in its entirety, and Tithonium Chasma 805 kilometers.

The orbiter is also equipped with 3D imaging capabilities, which reveal that, in this image, the canyon reaches about as deep as it can – around 7 kilometers, five times deeper than the Grand Canyon.

The topography of the two chasmata. (ESA/DLR/FU Berlin)

The topography of the two chasmata. (ESA/DLR/FU Berlin)

There are several features of note that the images reveal in the two chasmata. Within Ius, a row of jagged mountains probably formed as the two tectonic plates pulled apart. As that was some time ago, these mountains are pretty eroded.

Tithonium is partially colored a darker hue in the top part of the image. This may have come from the nearby Tharsis volcanic region to the west of the chasma. Paler mounds arise from within this dark sand; these are actually mountains that stand more than 3 kilometers tall.

However, the mountains' tops have been scoured off thanks to erosion. This suggests that whatever material the mountain is made of is softer and weaker than the rock around it.

That rock isn't impervious, either, though. To the lower right of the more visible of the mountains, features suggest a recent landslide of the canyon wall to the right.

An annotated map showing various features in the chasmata. (ESA/DLR/FU Berlin)

An annotated map showing various features in the chasmata. (ESA/DLR/FU Berlin)

Interestingly, Mars Express has detected sulfate-bearing minerals in some of the features within Tithonium Chasma. This has been interpreted as evidence that the Chasma was once (at least partially) filled with water.

The evidence is far from conclusive, but recent detections of hydrogen in the chasma suggest that a lot of water may be bound up with minerals beneath the surface.

As with most Mars science, it's difficult to make conclusions with any certainty, since we are forced – currently, at least – to study it remotely. But identifying areas of interest could help in the planning of future Mars missions, both crewed and uncrewed; sending a rover to Valles Marineris would certainly aid scientists in answering some of the burning questions that have arisen.

Images like these are scientifically useful because they help formulate and sometimes answer those questions. But they're also just spectacularly gorgeous.

The images have been published on the ESA website.