There is a supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy. There is also a lot of other stuff there as well. Young stars, gas, dust, and stellar-mass black holes. It's a happening place.

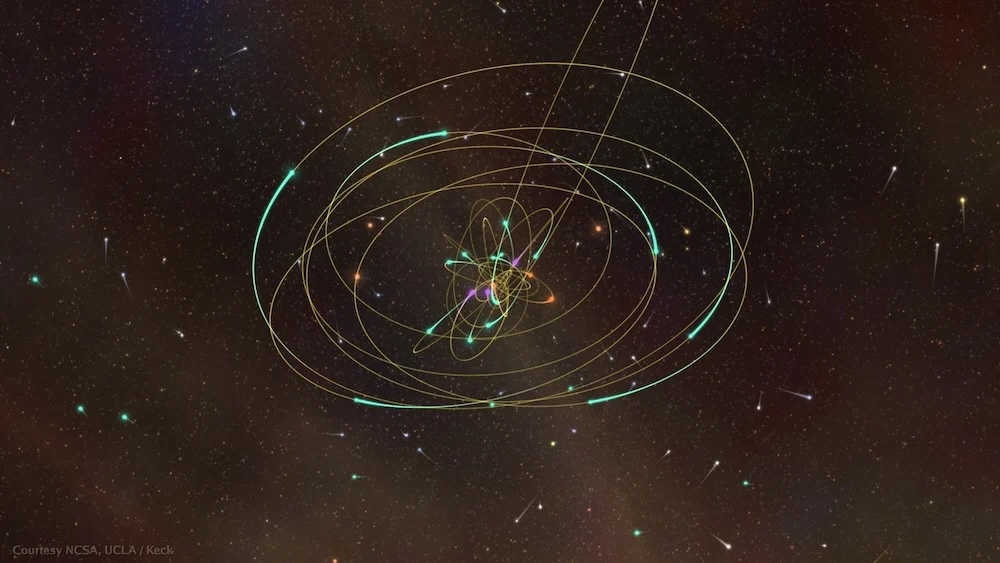

It is also surrounded by a veil of interstellar gas and dust, which means we can't observe the region in visible light. We can observe stars in the region through infrared and radio, and some of the gas there emits radio light, but the stellar-mass black holes remain mostly a mystery.

One big challenge is that we don't have a good measure of how many black holes are there. Traditional models of star formation suggest there may be as few as 300 in the closest region of the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A*.

Other models suggest that the formation of Sgr A* itself may have triggered the formation of hundreds of stellar-mass black holes. But a new study in Astronomy & Astrophysics suggests the number of stellar-mass black holes is much higher.

The idea behind this new model is that, compared to the rest of the galaxy, the central region near Sgr A* is dense with gas and dust. This means that large O-type and B-type stars can form easily.

These stars have very short lifetimes, and so would die as supernovae. Their cores would collapse into black holes, and the rest of their material would be cast off and available to make new stars. Over time, black holes in the region would accumulate as new cycles of stars were born and died.

Eventually, the region would become populated with enough black holes that collisions between stars and black holes would be common. Black holes would rip stars apart on a gradual basis, churning the region to accelerate star and black hole formation. The authors call this model the star grinder.

If this model is correct, then the center of our galaxy could have millions or billions of stellar-mass black holes per cubic parsec. Any star entering that region would do so at its peril. It's a fascinating idea, but how could we prove it? For this, the authors look to a statistical concept known as collision time.

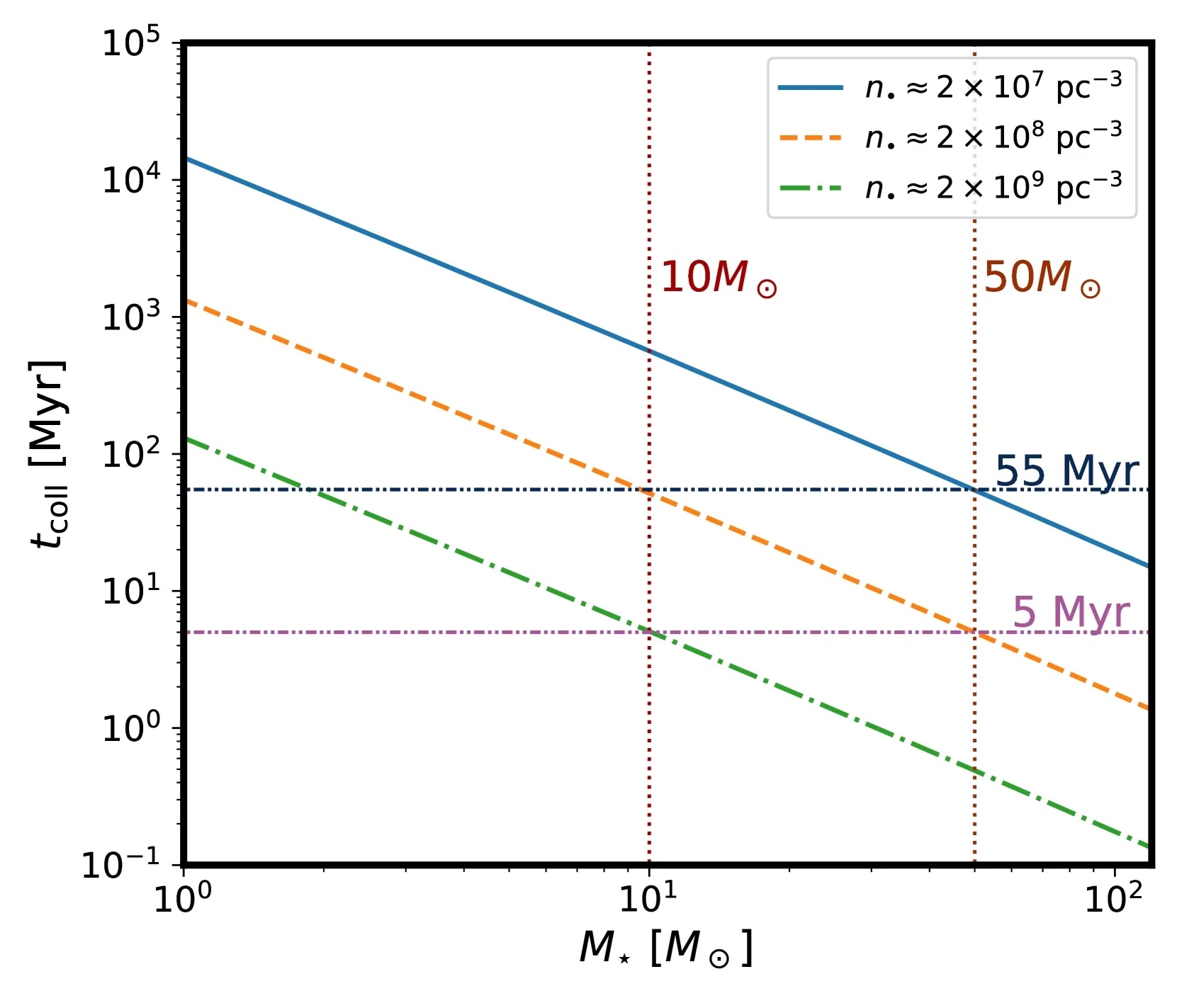

For a given density of black holes in the region, there is an average time before a star and black hole collide. This collision time depends upon the number of black holes in the region and the size of the star. Obviously, the higher the black hole count, the shorter the collision time, but also the larger the star, the more likely it is to have a collision.

The team calculated the collision times for various distributions, then compared their results to what we observe. Since the largest stars at the center of the galaxy are the easiest to detect, we have a good idea of how many there are. Based on observations, there are fewer of the largest O-type stars in the region compared with other parts of the Milky Way.

This suggests that O-type stars experience black hole grinding. There are plenty of the smaller B-type stars in the region, which suggests they don't encounter black holes often. Based on their statistics, the authors argue that there are about 100 million black holes per cubic parsec in the region around Sgr A*.

The authors also note that this model would explain the presence of hypervelocity stars in our galaxy's halo. We know of about a dozen stars with speeds so great they will escape our galaxy.

One way for a star to gain such speed is to have a close encounter with a black hole. The number of hypervelocity stars we observe could have been caused by close encounters at the center of the Milky Way.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.