One of the most recognisable star formations in our galaxy could be harbouring an intergalactic fugitive.

Hiding in the Ursa Major constellation, home of the Big Dipper, astronomers have recently ousted a strange star unlike any other in the Milky Way.

Officially known as J1124+4535, this bizarre celestial body appears to have an unusual chemical signature and, incidentally, origin.

Using a spectroscopic telescope in China that can analyse a star's light spectrum, researchers noticed this particular one contains a mere fraction of the magnesium and iron chemicals seen among its neighbours.

A follow up study on the Subaru Telescope in Japan confirmed the findings, while also revealing a curious abundance of a chemical called europium in the star, far more than even the Sun itself contains.

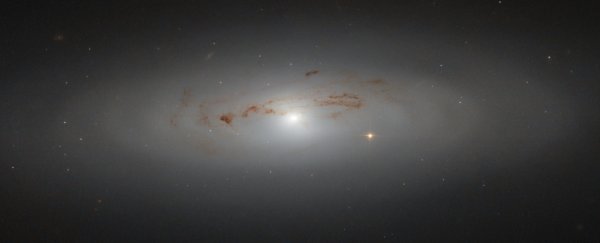

The ratio is unlike anything ever seen in the rest of the galaxy's stars, and it's got scientists thinking this one might be an intergalactic outsider, a lonely remnant of a dwarf galaxy that was once swallowed by our own.

"Stars like this one have been found in present-day dwarf galaxies," the authors explain, "providing the clearest chemical signature of past accretion events onto the Milky Way."

A star like J1124+4535 is extremely rare and an obvious outsider in our own galaxy, but that does not mean it is all alone in the Universe. Astronomers have recently observed other stars with similar low metal contents, flying around the periphery of the Milky Way.

What's more, the authors explain, stars that are formed in dwarf galaxies orbiting our own, like Ursa Minor (UMi), have kindred compositions as well, showing low levels of sodium, scandium, nickel and zinc.

"Stars form from clouds of interstellar gas," a press release on the discovery explains.

"The element ratios of the parent cloud impart an observable chemical signature on stars formed in that cloud. So stars formed close together have similar element ratios."

Because of their similarities, astronomers now think J1124+4535 must have come from an evolved and ancient dwarf galaxy, somewhat similar to UMi.

It's the first time we've ever seen something like this in our own galaxy, and it's been sitting under our noses the whole time.

This study has been published in Nature Astronomy.