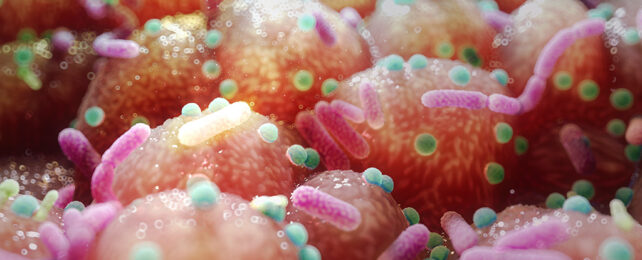

There's a whole world inside your gut, made up of mostly harmless microbes that reside in the gastrointestinal tract.

Called the gut microbiome, this dazzling collection of bacteria and other microorganisms has been the source of much attention – linked to a vast array of health conditions, from autism spectrum disorder and diabetes, to depression, Alzheimer's disease, and movement disorders.

But for all that researchers have discovered about the gut microbiome, there's a whole lot we still don't know – and a stack of myths it appears we need to clean up.

Writing in Nature Microbiology after scouring the literature, UK microbiologists Alan Walker from the University of Aberdeen and Lesley Hoyles from Nottingham Trent University weigh in on 12 myths and misconceptions about the gut microbiome, in part spawned by the huge potential the gut microbiome holds for human health.

"Although truly exciting, the increasing focus on microbiome research has unfortunately also brought with it hype and entrenched certain misconceptions," Walker and Hoyles write.

"As a result, many unsupported, or under-supported, statements have become 'fact' by virtue of constant repetition."

While some of these myths are relatively trivial, others are more widespread, and collectively, they could undermine progress and public confidence in the research, Walker and Hoyles argue.

So let's dive into some of the juicier myths on the list. Mind the mucus.

For starters, microbiome research is not some new field; it dates back to at least the late 19th century, when the first bacterial samples were isolated from the human intestine.

Similarly, the mysterious connection between the body's bowels and the mind, the gut-brain axis, has been researched for centuries. Only more recently have we come to appreciate how that connection operates in both directions.

Now for some numbers. The sum total of the human microbiota has been estimated to weigh between 1 to 2 kilograms (2.2 to 4.4 pounds). But Walker and Hoyles were unable to find the original source for this widely cited figure.

Instead, they calculate the human microbiota more likely weighs 500 grams or less. Their revised estimate is based on how much an average human stool weighs (200 grams wet weight), how much of that poop is made up of microorganisms (about half), and the weight of colonic contents.

Similarly, some 'back of the envelope' calculations in the 1970s gave rise to the idea that the human body houses 10 times as many individual microbes as its own cells.

Researchers have tried to clear up this myth before, finding that the ratio is probably closer to 1:1. Obviously, it bears repeating if we see those figures doing the rounds again.

Another commonly reported claim is that babies 'inherit' their microbiota from their mothers at birth. While some microorganisms are directly transferred during birth, research suggests few species actually stay with us throughout our lives.

A mother's microbiota might give babies a brief health boost, but it's our diet, antibiotics, genetics, and the environment we're exposed to that shape our microbiome.

"Every adult ends up with a unique microbiota configuration, even identical twins that are raised in the same household," Walker and Hoyles note.

The remaining misconceptions are a bit more technical, concerning the lab work of busy microbiologists.

But the last one we're probably most interested in is whether changes in a person's gut microbiome contribute to disease.

It's difficult for researchers to draw clear patterns because "such alterations are rarely consistent and the microbiota is hugely variable between individuals, both in health and disease," Walker and Hoyles write.

Age, BMI, and medication, as well as a person's metabolism and immune system, can also affect microbiota composition, which makes it all very challenging to disentangle any possible cause and effect in observational studies.

The perspective has been published in Nature Microbiology.