Earth is about to be lashed by solar storms, according to reports from several space weather agencies around the world.

Thanks to the double whammy of a high solar wind speed and several coronal mass ejections, we could be seeing a strong storm, as well as several moderate and mild ones, in the days ahead.

The British Met Office, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) have all issued advisories for solar – or geomagnetic – storms over the next few days, as an active sunspot region repeatedly released strong, M-class solar flares.

You have – to be clear – very little to worry about.

This is normal behavior from the Sun, particularly at the current stage of its 11-year activity cycle. These storms may cause some minor glitches in technology that you probably won't even notice – in fact, one moderate storm has already passed.

If, however, you live at or are visiting high latitudes, you probably have something very exciting to look forward to: an increased chance of the incredible aurora borealis or australis.

Solar storms are a natural and ongoing part of life with our magnificent dynamic Sun. Roughly every 11 years, it undergoes a cycle of varying activity levels, from low to high, and back to low again, when a new cycle kicks in.

These cycles can be observed in sunspot and coronal hole activity. Sunspot numbers increase towards the activity peak, known as solar maximum, and subside again towards solar minimum, the low end of the activity scale.

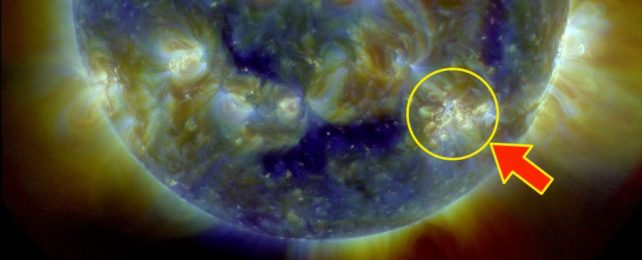

Sunspots are temporary regions on the Sun that have more powerful and complex magnetic fields than the regions around them. They are cooler, darker and less dense than the surrounding plasma. Their complicated magnetic field lines tangle, snap and reconnect; this reconnection produces an eruption of energy known as a coronal mass ejection, and sometimes solar flares.

Coronal holes are also cooler, darker and less dense than plasma, but they're much larger than sunspots, and the result of open magnetic fields that allow the solar wind to escape into space more easily. This results in relatively fast streams of solar wind.

Currently, the Sun has both going on. It's in the escalating stage of its activity cycle, ramping up to a peak predicted to occur in July 2025.

That means it has been pretty rowdy, with an eruption of some kind occurring so far almost every day this year.

Most of those have been pretty small. But the larger eruptions, such as the M-class flares emitted by the sunspot named AR3078, can have an effect on Earth if they're oriented in our direction. The plasma and magnetic fields ejected into space from these eruptions can collide with our magnetic field and atmosphere, resulting in a geomagnetic storm.

These have distinct classifications. A mild storm is classed as G1, and a G2 storm is moderate. Both BOM and the Met Office have predicted these.

In addition, the NOAA SWPC has predicted a potential G3 storm – a strong one. The scale goes all the way up to G5.

For mild storms, power grid fluctuations can occur, migratory animals are affected, and some satellite operations can experience minor effects.

For moderate storms, voltage alarms and transformer damage can occur, satellites may need course corrections, and high-frequency radio operations may be disrupted.

For a strong storm, voltage corrections may be necessary, satellites may experience surface charging, and satellite and low-frequency radio navigation may be disrupted.

In all three instances, aurora might be seen. These are the result of charged particles from the solar eruption hitting Earth's magnetosphere, and accelerating along the magnetic field lines to the poles. There, they rain down into the upper atmosphere, and interactions with molecules in the atmosphere cause the incredible auroral glow in the sky.

For a G3 storm, these lights may appear as low as 50 degrees latitude – as far south as Illinois and Oregon.

According to SpaceWeatherLive's aurora forecast, August 18 and 19 have maximum levels of Kp7 and Kp6 respectively on the 10-point Kp scale of geomagnetic activity. Stormy with a chance of bright, clear aurora borealis.

The Kaus index, for auroral predictions in the southern hemisphere, is significantly lower, according to BOM at the time of writing.

The AR3078 sunspot is moving away from us; its most recent M-class eruption will only graze Earth, if it hits us at all, and we'll be out of the strike zone of any further eruptions.

It is, however, only a matter of time before another set of solar storms hits.

The Sun is much more active than officially predicted this cycle, and has already unleashed several X-class flares this year. Those are the most powerful eruptions the Sun is capable of; M-class flares are the next level down.

To stay abreast of solar activity, you can follow the SWPC, the Met Office, BOM, and SpaceWeatherLive at their respective websites. You can also read more about solar flare classifications here.