Spare a thought for the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate, not long for this world (in tectonic plate terms) as it slowly slides under the continent of North America. Geologists are hoping it can help solve one of the biggest mysteries in their field – how tectonic plates die.

The Juan de Fuca plate is the last remnant of the much bigger Farallon plate, which has been disappearing under North America for tens of millions of years. It's the perfect opportunity to study how plates eventually get swallowed up, and how that might cause seismic and volcanic activity on the surface.

In particular, researchers William Hawley and Richard Allen, from the University of California, Berkeley, are interested in a gap that's appearing in the Juan de Fuca plate – which may in fact represent a tearing of the plate way down below the surface.

"The tearing not only causes volcanism on North America but also causes deformation of the not‐yet‐subducted sections of the oceanic plate offshore," write the researchers in their newly published paper.

"This tearing may eventually cause the plate to fragment, and what is left of the small pieces of the plate will attach to other plates nearby."

All the rock that gets buried as a plate is subsumed has to go somewhere, and the large-scale deformations and breaks that can occur aren't easy for scientists to predict or map.

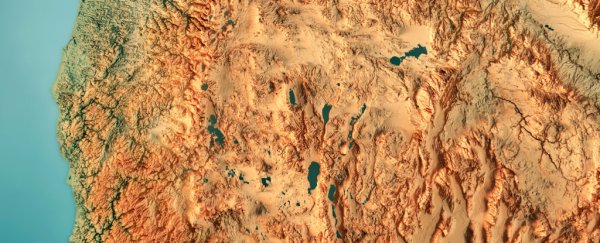

Using data from 217 earthquakes and more than 30,000 seismic waves, Hawley and Allen have been able to put together a detailed 3D picture of this particular part of the Cascadia Subduction Zone. Specifically, they identified which parts of the rock were from the Juan de Fuca plate.

They found what looks like a tear more than 150 kilometres (93 miles) deep, and it matches a previously identified area of weakness on the Juan de Fuca plate at the surface, known as a propagator wake.

The researchers suggest that as the Juan de Fuca plate turns and twists, parts of it are being pulled off and separated, creating the gap that experts have observed. Some of it might even live on as part of another plate.

More evidence is needed to be sure of what is happening here, but the hypothesis matches seismic activity around southern Oregon and northern California, as well as unusual patterns of volcanism in the region.

Those unusual patterns are the volcanoes known as the High Lava Plains in southern Oregon, where the newest eruptions are at the wrong end of the series from where geologists would expect them to be, based on the direction of drift of the North American tectonic plate.

Fresh volcanic activity caused by the propagator wake and deeper weakness in the Juan de Fuca could perhaps explain this anomaly, the researchers suggest.

As Juan de Fuca disappears, further research – as well as readings from the EarthScope project and the Cascadia Initiative, which were used in this study – should shed more light on how tectonic plates die, and how they've formed the world we live on.

"In many ways, when we're looking at these things, we're looking back in time," seismologist Lara Wagner from the Carnegie Institution for Science, who wasn't involved in the study, told National Geographic.

"If we don't understand how those processes work[ed] in the past, where we can see the whole story and study it, then our chances of seeing what's happening today and understanding how that might evolve in the future are zero."

The research has been published in Geophysical Research Letters.