For a condition that affects at least one in ten women of reproductive age and is a leading cause of female infertility worldwide, we understand surprisingly little about polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

At present, treatment for the condition focuses largely on managing specific symptoms.

Now a pilot clinical study led by Fudan University in China has found a pharmaceutical used to treat malaria shows promise as a PCOS treatment, shrinking oversized follicles and returning regularity to some participants' periods.

The medication is a synthetic version of the herbal form of artemisinin. Derived from Artemisia annua (known commonly as 'sweet wormwood' or 'qinghao'), it originated as an ancient Chinese herbal therapy to treat fevers associated with the parasitic disease.

They tested the effects of artemisinins – first artemether in rats in which the condition was induced, and then a metabolite of the compounds called dihydroartemisinin in humans with PCOS – on testosterone levels, the menstrual cycle, and other physical symptoms of PCOS.

For malaria, dihydroartemisinin is often given in combination with another anti-parasitic drug. In this pilot study it was given alone; 40 mg three times daily for 12 weeks.

The researchers found dihydroartemisinin effectively treated PCOS symptoms by preventing the ovaries from producing excess quantities of the androgen testosterone, one hormone believed to drive PCOS symptoms, as well as another that has been linked to PCOS, anti-Müllerian hormone.

Infertility is, for many, the most concerning of these symptoms, which can also include missed, irregular, or unusually painful periods, ovarian enlargement and cysts, excess body hair, weight gain, skin troubles, thinning hair, and mood swings.

The artemisinin treatment interrupts androgen production by getting in the way of a key chemical reaction that produces steroids. With artemisinin interfering with the production of testosterone, the androgen's levels in both humans and rats fell.

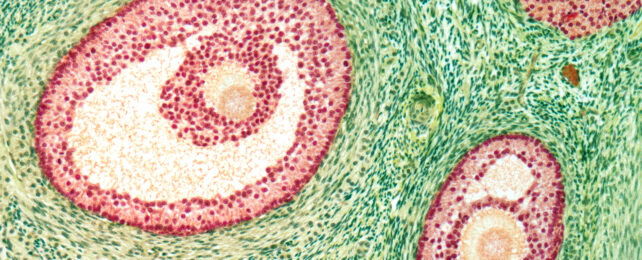

That drop led to a reduction in menstrual abnormalities – 12 of the participants actually resumed normal periods following the treatment – along with a reduction in antral follicle count and size, which is a measure of how 'cystic' an ovary is.

The treatment also reduced anti-Müllerian hormone levels, which was expected as androgen-induced increases in these antral follicles appear to contribute to higher levels of the hormone.

Though promising, more research will be needed given that the pilot clinical trial involved only 19 Chinese women with PCOS, all around 28 years of age.

"Further studies will be needed to fully understand the long-term effects and to optimize dosing strategies to maximize therapeutic outcomes," writes endocrinologist Elisabet Stener-Victorin from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, in her perspective article on the paper.

"The discovery of artemisinins as effective remedies for PCOS nonetheless represents a promising new approach for the development of specific therapies that will potentially change the landscape of PCOS treatment."

This research has been published in Science.