Joanie Simpson woke early one morning with a terrible backache. Her chest started hurting when she turned over.

Within 20 minutes, she was at a local emergency room. Soon she was being airlifted to a hospital in Houston, where physicians were preparing to receive a patient exhibiting the classic signs of a heart attack.

But tests at Memorial Hermann Heart & Vascular Institute - Texas Medical Center revealed something very different.

Doctors instead diagnosed Simpson with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, a condition with symptoms that mimic heart attacks. It usually occurs following an emotional event such as the loss of a spouse or child. That link has given the illness its more colloquial name: broken-heart syndrome.

In Simpson's case, the event that she says tipped her over the edge was the recent death of her beloved Yorkshire terrier, Meha.

"I was close to inconsolable," she said. "I really took it really, really hard."

Meha. Image: Joanie Simpson

Meha. Image: Joanie Simpson

Simpson's 2016 experience is described this week in the New England Journal of Medicine — not because of the dog's role, according to one of her doctors, Abhishek Maiti, but because hers was a "very concise, elegant case" of a fascinating condition that research has established as quite real and sometimes fatal.

Although not the first published case linking broken-heart syndrome to stress over a pet's death, it underscores something many animal owners take as a given: that grieving for sick or deceased pets can be as gutting as grieving for humans.

A growing body of research supports this notion, which was echoed in a recent study that found pet owners with chronically ill animals have higher levels of "caregiver burden", stress and anxiety.

It's the flip side of evidence that links pets to health and happiness, which gets more attention. Not that people who have lost beloved animals are likely to be surprised.

Simpson certainly wasn't shocked. At the time of what she calls her "episode," she'd been having a rough stretch: Her son was facing back surgery. Her son-in-law had lost his job. A property sale was proving to be complicated and lengthy. Meanwhile, 9-year-old Meha was suffering from congestive heart failure.

The dog was like a daughter, Simpson said. She adored jumping into the swimming pool, and when Simpson and her husband grilled on Friday nights, Meha was given her own hamburger.

"The kids were grown and out of the house, so she was our little girl," said Simpson, a 62-year-old retiree who previously worked in medical transcription.

But Meha started having more bad days. By May of last year, she was ill enough that Simpson made an appointment to have her euthanized. When the day came, the dog seemed fine, and Simpson canceled the appointment. Meha died the next day, and not peacefully.

"It was such a horrendous thing to have to witness," recalled Simpson. "When you're already kind of upset about other things, it's like a brick on a scale. I mean, everything just weighs on you."

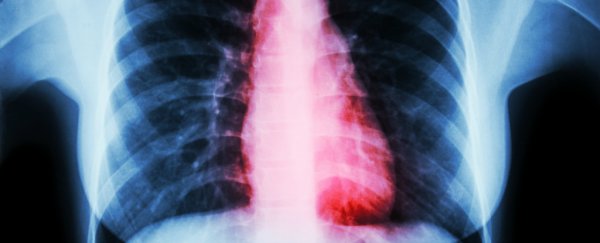

After the helicopter carrying Simpson landed on the roof of Memorial Hermann, she was rushed to the cardiac catheterisation lab. Cardiologist Abhijeet Dhoble quickly threaded a thin tube into a blood vessel in Simpson's groin and up to her heart.

The team expected X-rays to show blocked arteries, said Maiti, then an internal medicine resident. They didn't.

"The artery was crystal clear. It was pristine," he said. Another artery was, too. Further tests indicated this was a case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, which is most common in postmenopausal women.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2005 is among those that confirmed that a flood of stress hormones may be able to "stun" the heart to produce spasms in otherwise healthy people.

Once medications stabilised Simpson, the physicians talked to her about the stress in her life, and they told her about broken-heart syndrome. It "made complete sense", Simpson said. She was sent home after two days, and though she still takes two heart medications, she is doing fine.

Simpson, who now lives about two hours northwest of San Antonio in the town of Camp Woods, only has a cat named Buster these days. She hasn't yet made the right connection with a dog, though she's sure it will happen.

She is the kind of person who takes "things more to heart than a lot of people," she said, and she figures this tendency means her heart will break again, though maybe not so literally.

And it will be worth it, Simpson said.

"It is heartbreaking. It is traumatic. It is all of the above," Simpson said. "But you know what? They give so much love and companionship that I'll do it again. I will continue to have pets. That's not going to stop me."

2017 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.