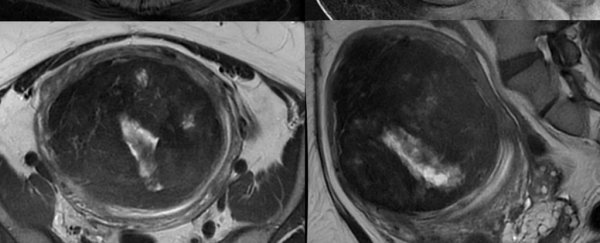

When a 53-year-old woman showed up at the hospital, a mass that first appeared in her uterus many years ago had grown to 61 pounds — roughly the weight of an average-size second grader.

Singaporean doctors have successfully removed the abnormally large mass also known as a uterine fibroid or leiomyoma, a tumor that appears in the uterus during a woman's childbearing age and grows gradually over the years if left untreated.

A uterine fibroid, a common pelvic tumor, is not cancerous, but it could be life-threatening if it grows exponentially and deforms surrounding organs, according to a report on the case recently published by the medical journal BMJ Case Reports.

The report describes the unnamed patient as a menopausal Malay woman who is "virgo-intacta" (translation: "untouched virgin").

When she arrived at the KK Women's and Children's Hospital in Singapore, she was bedridden and unable to move, and the mass had taken over most of her abdominal and pelvic cavities.

She also had been struggling to breathe for six months because air had not been able to travel freely to her lungs, according to the report, published Tuesday.

The woman did not seek medical attention sooner likely because she was afraid of surgery, Poh Ting Lim, an OB/GYN resident at the KK Women's and Children's Hospital, told Live Science.

The woman underwent several major operations to remove the mass, which is about 25 inches long across its widest point, as well as her uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes.

Afterward, she underwent a plastic surgery to reconstruct her abdominal wall, which had significantly thinned because of the mass, the report says.

Uterine fibroids are the most common pelvic tumor among women, particularly among those ages 50 and older. Most women don't know when they have the tumor because it rarely causes symptoms and hardly ever develop into cancer.

In cases in which symptoms occur, women experience heavy and lengthy menstrual periods, pelvic pain, constipation and frequent urination.

The Malay woman didn't experience these symptoms, the report says. Lim told Live Science that the woman may have avoided these symptoms because the tumor grew slowly, allowing her body to adjust to it. Lim didn't respond to an email from The Washington Post on Saturday seeking comment.

The report did not say how long the tumor had been growing in the woman's uterus. She was discharged a week after surgery.

Two months later, she's no longer struggling to breathe, she's able to move by herself and her abdominal scar from the operation has healed, the report says.

Fibroids' sizes vastly differ, from tiny dots undetectable by the human eye, to bulky masses that can enlarge the uterus, according to the Mayo Clinic. When a woman is at a childbearing age, the tumor grows slowly at a rate of 9 percent over six months, the report says.

Giant uterine fibroids rarely weigh more than 25 pounds, the report says.

Extreme cases, like that of the Malay woman, are rare because most growths are detected by doctors during routine exams, or when women experience symptoms.

The largest uterine fibroid on record weighed 139 pounds, which was removed after the patient died. The largest fibroid known to have been removed from a living patient weighed 100 pounds, the report says. Both cases happened in the late 1800s.

In more recent history, a 59-pound uterine fibroid was removed from a 47-year-old premenopausal woman in 2009, the report says. Another case was reported in 2011, when 25 pounds of the same noncancerous mass was removed from a 33-year-old woman.

Doctors don't know what causes uterine fibroids, but research points to factors such as genetic changes and hormones. Estrogen and progesterone "appear to promote the growth of fibroids," according to the Mayo Clinic.

Factors such as heredity and race also influence a woman's likelihood of developing uterine fibroids.

A woman whose mother and sister had fibroids is likely to also develop them. They're also most prevalent among African American women who are diagnosed with uterine fibroids at an earlier age and show evidence of more severe cases.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.